“Can you help us in identifying where our birds were made?”[1] This inquiry is one of numerous others regarding two fowl from a 1968 letter from Catherine Lynn Frangiamore, then an assistant in the Department of Decorative Arts (now Product Design and Decorative Arts) at Cooper Hewitt, to Lino Sandonnini, then director of the Museo Civico in Modena, Italy. Frangiamore’s question came months after the Smithsonian had adopted the collection of the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration in 1967. Two turkeys—wooden and gilded—had waddled into the collection in 1931 as a gift of the museum’s founders Eleanor and Sarah Hewitt, but little was confirmed of their origins.

While it is yet unknown the original maker or purpose of the two foul, they were inscribed as part of an attempted inventory process at the Palazzo Reale di Modena in 1842, as one of the figures reads: “No. 7671 / Inventarios Generale 1842 / Palazzo Reale di Modena.” However, the Inventarios Generale 1842, as it was called, was incomplete and made no account for the two seemingly orphaned turkeys. In response to Frangiamore’s letter, Filippo Valenti, then director of the State Archive of Modena, reported that only two volumes of the inventory were extant, registering objects only up to no. 7400. He enumerated: “If another record had existed, now lost, or in truth if, in the era in which the inventory was effected, the registration was not finished of all the personal property already labelled.”[2] A sort of tryptophan may have set in before our two turkeys got a shout out in the inventory.

Possible to confuse as peacocks, these highly stylized beasts of feather are likely ocellated turkey, notably for their two rows of eyed feathers and nobly bald rather than crested heads.[3] These turkeys are native to the Yucatan Peninsula, so it is not directly clear how a craftsperson on Italy’s booted peninsula would come to know or even imagine such a creature. But global trade was active in Italy, and the collection from whose aforementioned inventory they were noticeably excluded possesses a worldly scope certainly defiant of such geographic distinctions. In 1630, Duke Francesco I D’Este began building the Palazzo Ducale in Modena, and would bring to the palace a famed collection of decorative arts, painting, and sculpture with his ambitious and discerning eye. The toll of a few centuries—including a sale to the Elector of Saxony, some inevitable Napoleonic pillages, some neighborly pillaging from local churches, and the acquisition of the Obizzi collection—ruffled and shaped the collection. In 1894, the collection of the Galleria Estense Modena was reorganized and reopened for public viewing at the Palace Museum in Modena.[4] The Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration was founded by Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt three years later in 1897, with similar objectives of decorative arts adoration and public edification.

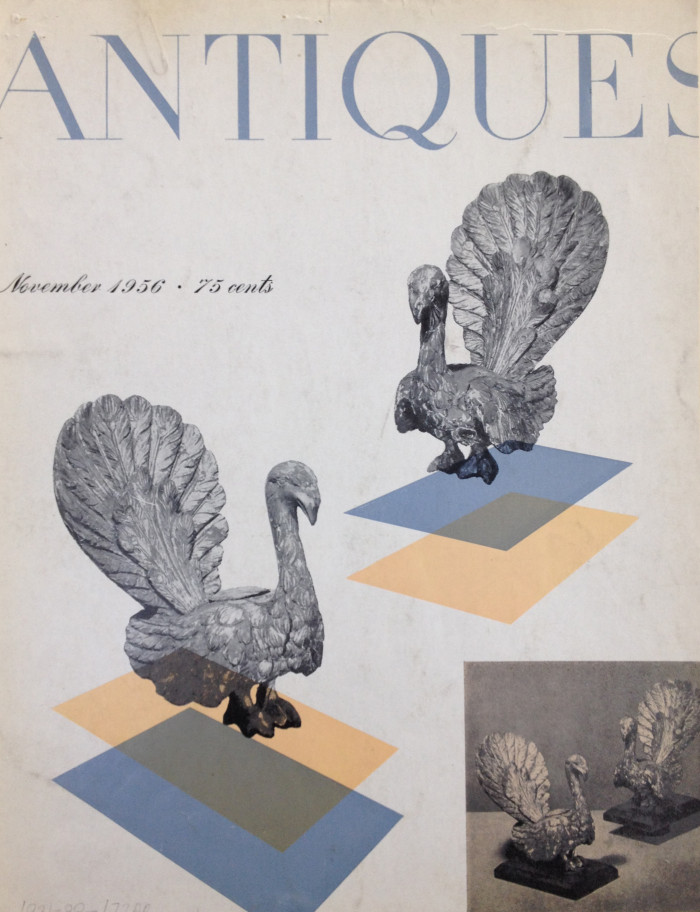

While the question of “where?” for these two turkeys remains, the scrupulous hawk eyes of the Hewitt sisters undoubtedly knew—through their extensive research, travels, and collecting—of the turkeys’ regal provenance and sought their acquisition for Cooper Union’s collection of decorative arts in America. And while not from a ducal inventory, the turkeys’ documentation does continue into the twentieth century, appearing festively in turkeys’ new role as holiday mascots on the November 1956 cover of the Magazine Antiques.

[1] “Hewitt, The Misses, Gilded Wood Italian Wood Turkies,” Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Email correspondence with Paul R. Sweet, Collections Manager, Vertebrate Zoology, Ornithology, American Museum of Natural History, November 17, 2016.

[4] “The Collections,” Galleria Estense Modena, accessed November 21, 2016, www.galleriaestense.org.

Matthew J. Kennedy is the publications associate at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, and personally wishes you a happy Thanksgiving.