In last month’s Short Story, Ringwood Historian Sue Shutte cleverly drew parallels between the collections of Ringwood Manor and Cooper Hewitt, giving insight to the Hewitt family’s personal style. In this month’s short story—or more of a collection spotlight—we look at more passions of Sarah and Eleanor and how they emanate through Cooper Hewitt’s collection: passions for theater, performance, and associated design.

Margery Masinter, Trustee, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Sue Shutte, Historian at Ringwood Manor

Matthew Kennedy, Publishing Associate, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Strike a Pose: Tableaux Vivants and Domestic Theatricals

In 1883, Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt attended the Vanderbilt Ball. This extravagant gala—involving elaborate costume and decoration at the Vanderbilt Mansion at 660 Fifth Avenue—was the social event of the Gilded Age. It also proved to be a formative experience for Sarah and Eleanor in their approach to fusing their theatrical interests with social entertainment.

(left) Sarah in costume at the Vanderbilt Ball, 1883. (right) Eleanor pictured in the costume she wore to the Vanderbilt Ball, 1890.

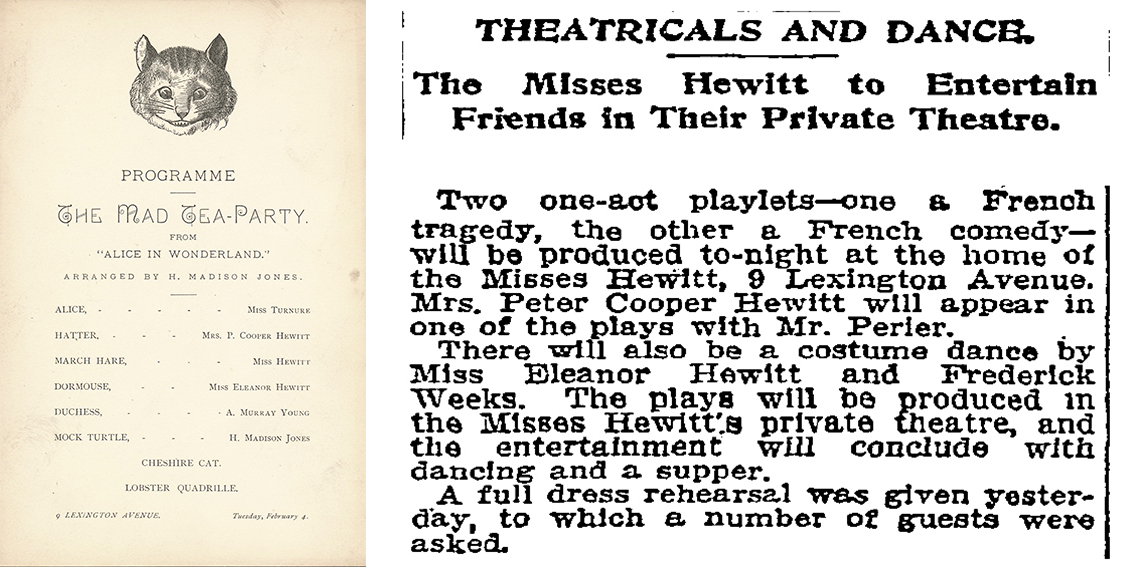

On our Meet the Hewitts blog, we wrote about the novel entertainments, concerts, and playlets the Hewitts staged in their unique private home theater at 9 Lexington Avenue in New York City. The New York Times heralded these events as some of “the most amusing entertainments” of the New York social scene. The spectacles often employed themes to further enliven the amusement, such as a well-received flower and vegetable party in 1898, in which “guests impersonated familiar garden flowers and vegetables.” Other themes included parades of nations and congresses of the four seasons, the latter also featuring some guests costumed “in white, trimmed with Spring flowers, and carrying a garland of clover blossoms” to personify Spring. An imaginative sartorial potpourri!

The Hewitt home boasted ample room for such boisterous festivities. While contemporary guests may be impressed with your surround-sound system, plush reclining chairs, or HD to the extreme, the Hewitt home theater—renovated and enlarged in 1903—featured a full orchestra pit (reportedly capable of fitting as many as fourteen musicians) and stalls (orchestra-level seats). However, Abram Hewitt passed away shortly after, and the family recessed into mourning, leaving the theater to limited use. It wasn’t until 1908 that they would host another large-scale soirée—for which the city was agog! The day following the ball, the New York Times reported on the event proclaiming “Novel Entertainment for 300 Guests”—an audience size larger than most Off-Broadway and many region theaters in the United States today. The evening’s entertainment included comedies previously presented at the Comédie Français in Paris; at this performance, the Hewitt’s sister-in-law Lucy Work played the lead, while Eleanor contributed a dance number.

Sarah and Eleanor were known as “clever amateur actresses” and took delight in creating original history and theme plays and parties. Guests were often asked to come and participate in costume, forming their own tableaux vivants—standing together in costume to create a spectacular visual presence. The Times again described one of these, of a 1909 event: “The groupings in the tableaux were most effective, and the rich costumes and striking contrasts in color gave the little comedy a gorgeous setting.” These theatrical events would begin at ten o’clock in the evening, followed by supper and dancing into the early morning hours.

The costumes pictured above were custom confections for the Vanderbilt Ball, but for these domestic theatrical performances the sisters often raided their mother and grandmother’s closets, so to speak, often for an authentic (what we might call “vintage”) look. The Times reported: “Mrs. [Peter Cooper] Hewitt [Sarah and Eleanor’s sister-in-law and frequent comedy performer] wore an old rose-colored brocade gown, with hoop-skirts, trimmed with lace…The gown was an heirloom in the family, and was worn by one of her ancestors.” At the same performance, Eleanor donned “a blue gown with crinoline, once worn by her grandmother on formal occasions, trimmed with ermine, and wore a large white bonnet and carried an ermine muff.” The performances in question were set in the 1830s and 40’s, and thus the performers had to be outfitted in appropriate garb of that era. (As dedicated design historians, the Hewitts certainly needed to literally act the part.)

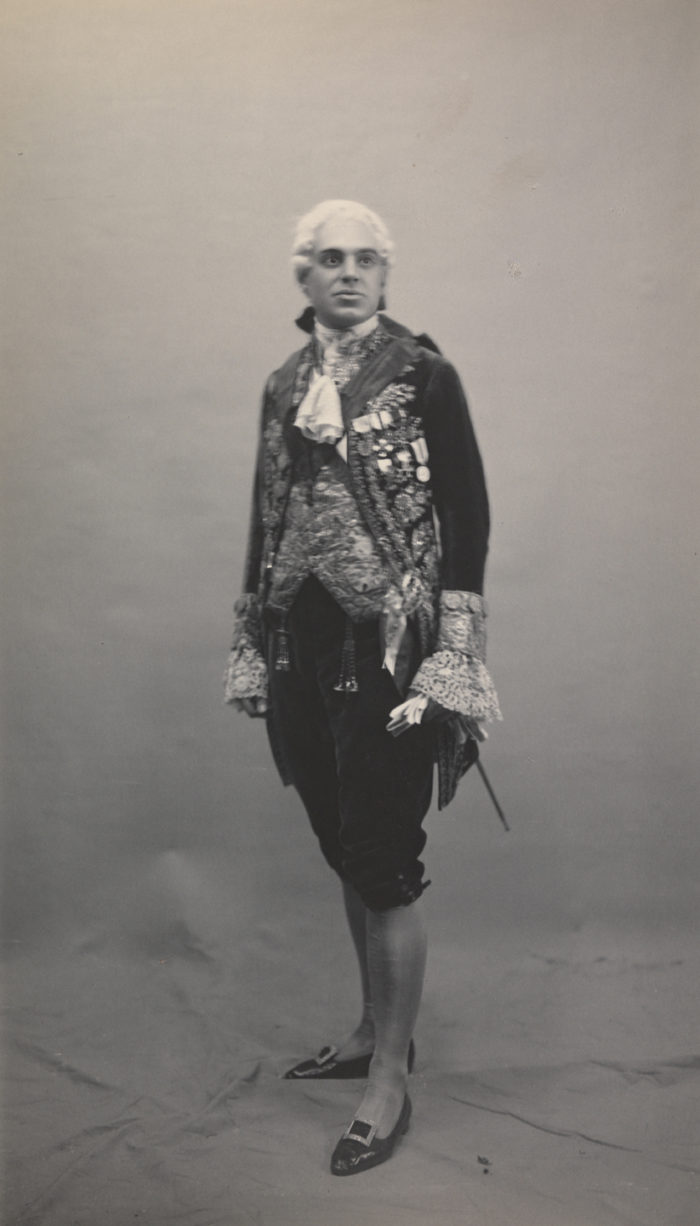

Erskine Hewitt (1871–1938) was Sarah and Eleanor’s youngest brother. As would be expected, he participated in these spectacles (mostly planned by his sisters and mother), festively attired below for a 1905 tableaux. A lawyer, collector, and philanthropist, he contributed over 3,200 drawings and prints to his sisters’ Cooper Union Museum, including more than seventy-five designs related to theater.

Portrait of Mr. Erskine Hewitt at the James Hazen Hyde Ball, January 31, 1905. Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

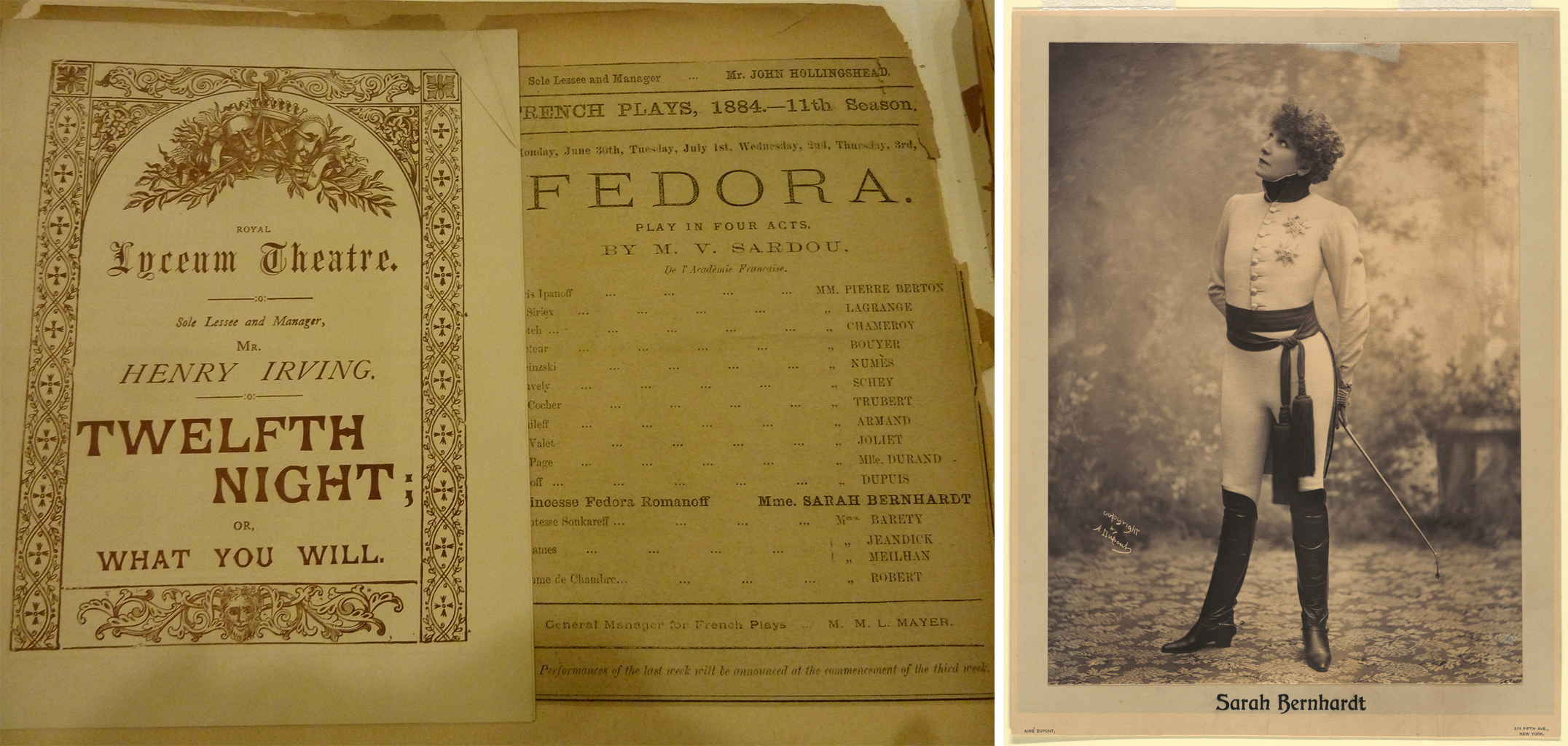

Outside of their own theatrical performances, the Hewitts frequently added the theater. The sisters’ favorite performer was the widely acclaimed French actress Sarah Bernhardt, and they coveted programs of her performances in their scrapbooks. Also in their scrapbooks of theatrical ephemera are multiple programs for performances of Helena Modjeska, a renowned Polish dramatic actress who vacationed with the Hewitts at their country estate, Ringwood Manor.

(left) Scrapbook clippings of Bernhardt in Fedora by Victorien Sardou, 1884. (right) Photograph, Sarah Bernhardt as the Duke of Reichstadt (later King of Rome), ca. 1900; Aimé Dupont (1842–1900); Platinum print support: sensitized white wove paper, laid down on thick white wove paper; 34.4 x 25.3 cm (13 9/16 x 9 15/16 in.); Mount: 38.9 x 29.3 Mat: 45.7 x 35.6 cm (18 x 14 in.); 1953-187-2

Raising the Curtain: Cooper Hewitt’s Continuing Theatrical Collection

(left) Drawing, Three Rockettes, 1935; Christina Malman (American, b. England, 1911–1959); Pen and india ink, brush and white heightening, graphite on cream paper; 29.9 x 31.9 cm (11 3/4 x 12 9/16 in.); Gift of Dexter Masters, 1960-214-31. (right) Poster, An American in Paris, Théâtre du Châtelet, 2014; Designed by Philippe Apeloig (French, b. 1962); Screenprint on paper; 175 x 118.5 cm (5 ft. 8 7/8 in. x 46 5/8 in.); Gift of Philippe Apeloig in honor of Gail Davidson, 2015-34-2

Continuing the Hewitt passion for performance and entertainment—and its fanciful accoutrements—Cooper Hewitt collects an impressive range of designs related to the theatrical arts, including stage designs, costume designs, prints of theater architecture, and theater posters. The collection casts designs for productions of the plays of William Shakespeare, musicals and vaudeville, opera, and more. These pieces primarily span the seventeenth through twentieth centuries.

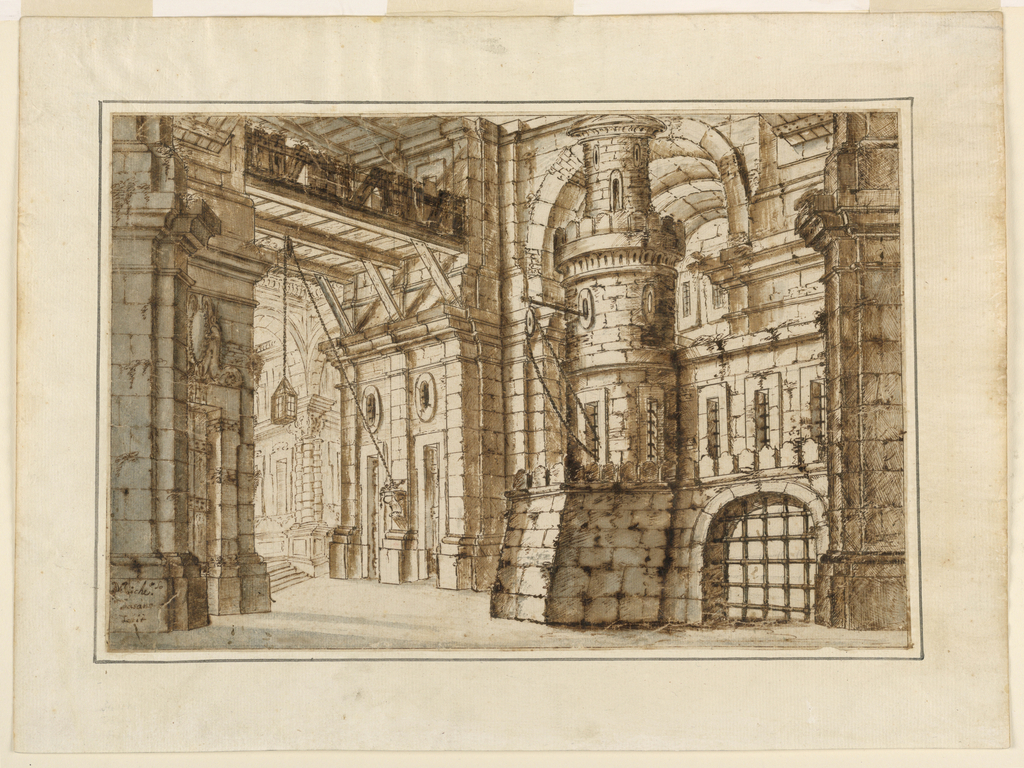

The largest segment of theatrical design in the museum’s collection consists of European stage designs from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. These came from the collection of Italian artist and collector Giovanni Piancastelli, a sale originally initiated by Sarah and Eleanor in 1901.

Drawing, Stage Design of a Prison Interior, mid-18th century; Designed by Michelangelo Fasano (Italian, active 18th century); Pen and brown ink, brush and gray-blue wash over black chalk on laid paper, lined; 26.6 x 39.6 cm (10 1/2 x 15 9/16 in.); Museum purchase through gift of various donors and from Eleanor G. Hewitt Fund, 1938-88-35

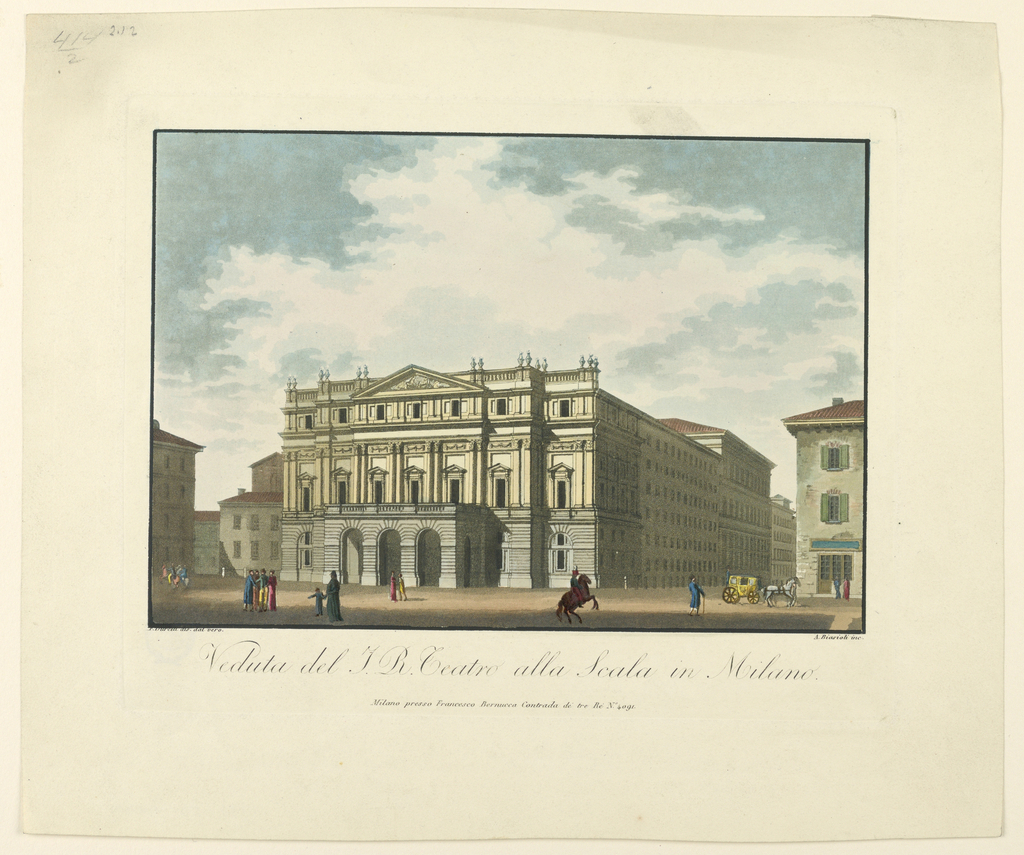

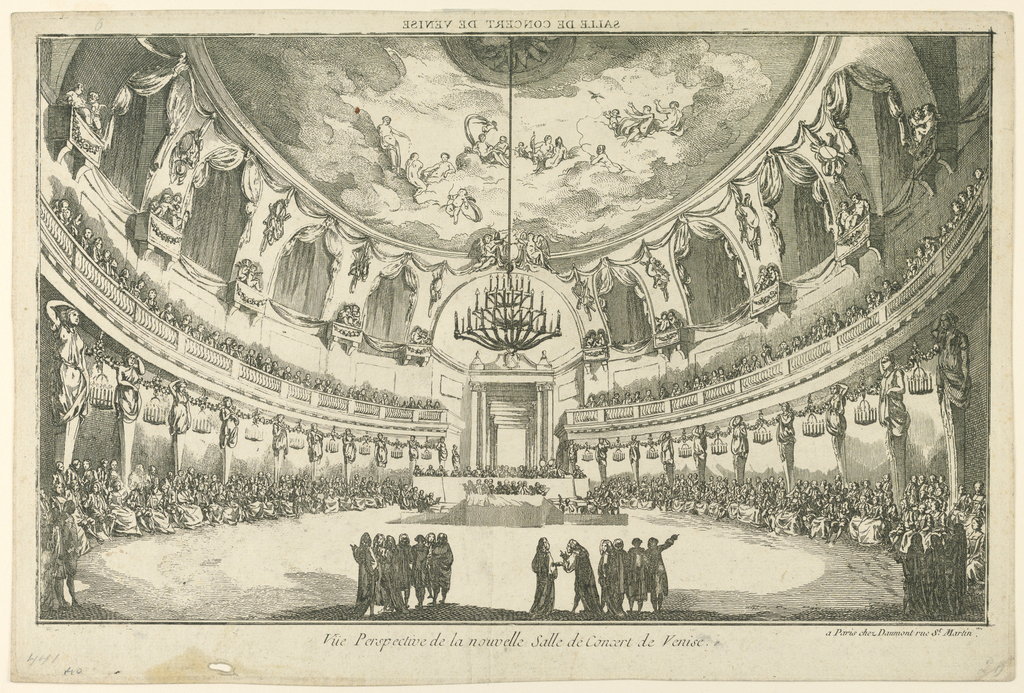

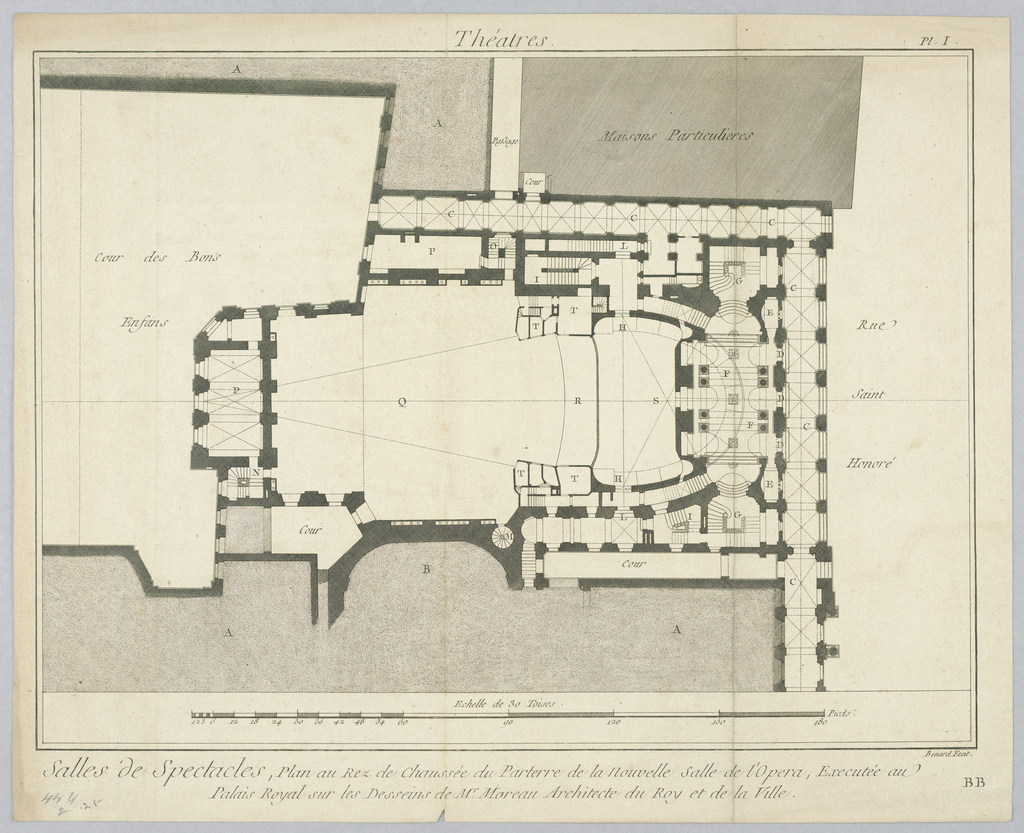

In Erskine’s substantial gift to the museum in 1938, he contributed more than seventy-five architectural drawings and prints relating the theaters. Prints of iconic structures, such as La Scala in Milan, Italy, commemorate civic magnitude while floorplans of theatrical interiors reinforce the practical bones of the theater-going experience and often the social hierarchy imposed at such events.

Print, La Scala Theater, Milan, 1815–30; Designed by Angelo Biasoli (1790–1830); Aquatint engraving; Platemark: 18.6 × 23.1 cm (7 5/16 × 9 1/8 in.); 24.7 × 29.5 cm (9 3/4 × 11 5/8 in.); Bequest of Erskine Hewitt, 1938-57-1432

Print, Interior of the New Concert Hall, Venice, 1760–90; Etching on paper; Platemark: 27.3 × 41 cm (10 3/4 × 16 1/8 in.); 27.6 × 41.3 cm (10 7/8 × 16 1/4 in.); Bequest of Erskine Hewitt, 1938-57-1411

Print, Plan of the Ground Floor and the Pit for an Opera House, 18th century; Designed by Robert Bénard (French, active 1734–1772); Engraving on paper; Bequest of Erskine Hewitt, 1938-57-1407

More recent acquisitions have included twentieth-century costume designs, frequently referencing an array of historical costume styles. As the Hewitts often dug into their family’s past wardrobes to capture a historical moment of their performances, costume designers borrow past forms to similarly convey historical sensibilities in service of character and narrative.

(left) Drawing, Costume Design: Nora, Act I, A Doll’s House, 1937; Designed by Donald Mitchell Oenslager (American, 1902–1975); Brush and watercolor, graphite on white paper with attached fabric swatches; 35.2 x 25.7 cm (13 7/8 x 10 1/8 in.); Gift of Donald Oenslager, 1960-226-11-b. (right) Drawing, Costume Design: The Pirates of Penzance, 1968; Designed by Patton Campbell (American, 1926–2006); Brush and watercolor, graphite on paper with attached trim sample; 37 × 28 cm (14 9/16 in. × 11 in.); Gift of Patton Campbell, 1970-53-2

Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House (1879) is set in Norway in the late 1870s; the comedic opera The Pirates of Penzance takes place during the more chronologically flexible period of Queen Victoria’s reign (a magisterial and majestic sixty-four year). Not to put Oenslager and Campbell’s designs under the scrutiny of historical accuracy (as both are fiction), but the costumes bear striking resemblance to the silhouettes, details, and palettes of Sarah’s own wardrobe from the period and cartoons by Hewitt friend Caroline King Duer in the Ringwood guest book entry from 1918, demonstrating a range of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century style and subsequent interpretation.

“Going to dinner,” probably Caroline King Duer, October 19, 1918, from the Ringwood Manor Guest Books. Courtesy of Ringwood Manor.

Sarah Hewitt’s Walking Suit, ca. 1889; Charles Frederick Worth (French, b. England, 1825–1895) for House of Worth (Paris, France); Silk; Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of the Princess Viggo in accordance with the wishes or the Misses Hewitt, 1931; 2009.300.73a,b

Costume designs for Hello, Dolly! by Freddy Wittop and The Unsinkable Molly Brown by Miles White further capture an ebullience and decadence of turn-of-the-century America, as interpreted through a midcentury lens. The designs project optimism in the face of uncertainty or catastrophe (particularly in Molly Brown’s case of the very sinkable Titanic) uniquely expressed through the maturing art form of musical theater in the 1950s and 60’s.

(left) Drawing, Costume Design: Hello, Dolly!, 1964; Designed by Freddy Wittop (American, b. Netherlands, 1911–2001); Brush and watercolor, graphite on gray paper; 43 x 46.2 cm (16 15/16 x 18 3/16 in.); Gift of Freddy Wittop, 1971-1-10. (right) Drawing, Costume Design: The Unsinkable Molly Brown, 1960; Designed by Miles White (American, 1914–2000); Pen and ink, brush and watercolor on paper; 34.6 × 25 cm (13 5/8 × 9 13/16 in.); Gift of Miles White, 1971-4-6

In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, blends of bold colors and intricate patterns invaded Western aesthetics as designers across media took inspiration from other world cultures—a result of large-scale globalization, industrialization, and colonization. One of the chief proponents of this in the dramatic arts was influential ballet company Ballet Russes, which, particularly through the set and costume designs of Leon Bakst, popularized “oriental” fashions in Paris and throughout Europe and the United States.

Drawing, Costume Design: Two Pirates, for Daphnis et Chloe, 1913; Leon Bakst; Brush and watercolor, graphite on illustration board; 26.8 x 39.5 cm (10 9/16 x 15 9/16 in. ); Gift of Mrs. G. Macculloch Miller, 1947-77-2

These palettes and parodies paraded through the twentieth century as productions were restaged or themes resurfaced when others looked to similar inspiration.

(left) Drawing, Costume Design: Eunuch, from Scheherezade, 1941; Designed by Richard Rychtarik (1895–1982); Pastel on paper; 1975-8-1. (right) Drawing, Costume Design: Slave, for Salome, 1955; Designed by Jay Keene; Brush and watercolor on wove paper; 34 × 24.7 cm (13 3/8 × 9 3/4 in.); Gift of Jay Keene, 1970-51-4

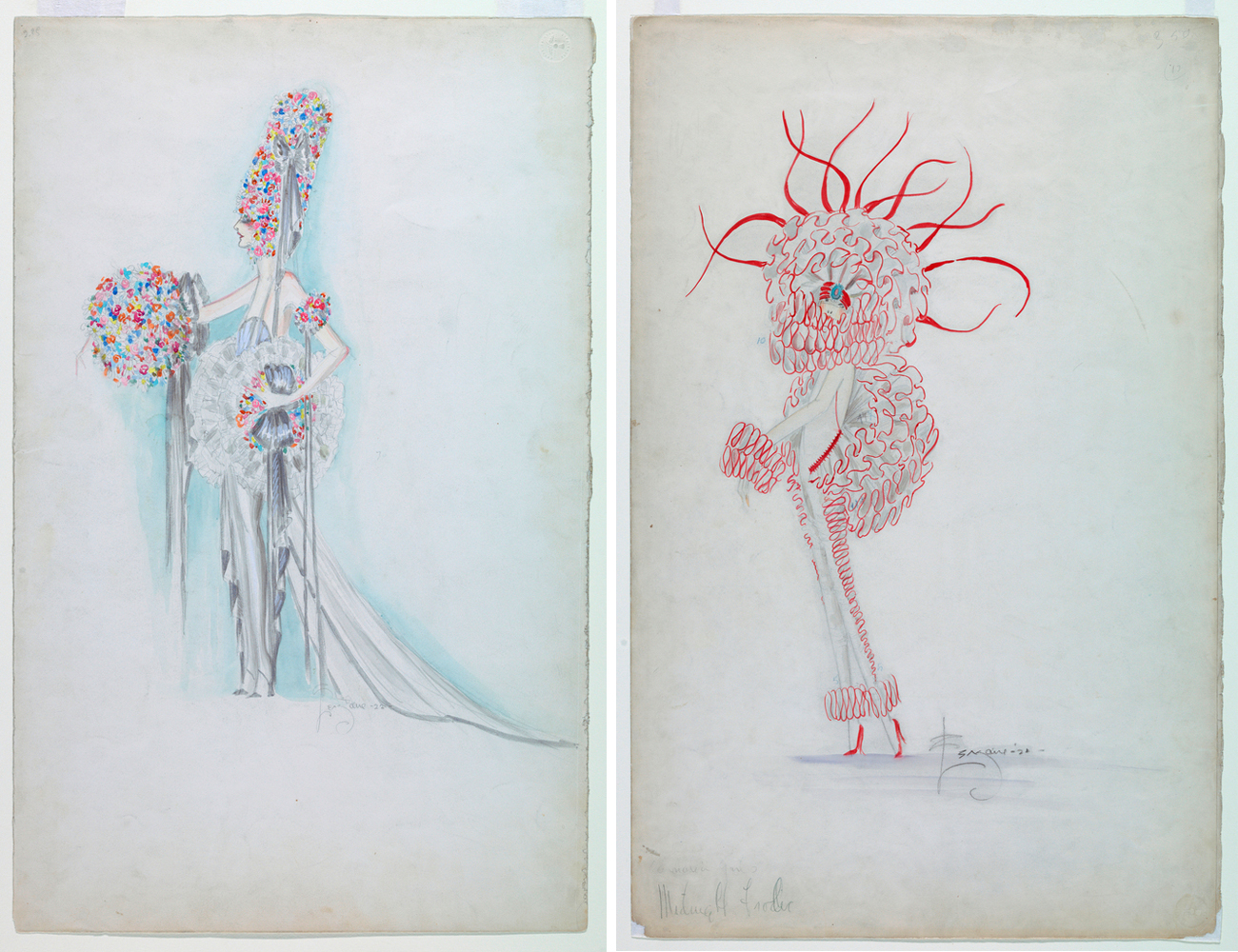

And not to neglect the bizarrerie… Charles LeMaire started in vaudeville—first as a performer, then as a costume designer—before moving to Hollywood and becoming head of wardrobe at 20th Century Fox film studio. He donated to Cooper Hewitt his designs for the Ziegfeld Follies of the early 1920s that reflect an imaginative approach costume design, looking to nature as well as fantasy and incorporating whimsical elements. These costumes may have been quite a natural fit at the aforementioned vegetable- and flower-themed extravaganza hosted by the Hewitts!

(left) Drawing, Costume Design: Ziegfeld Follies of 1922, 1922; Design by Charles LeMaire (American, 1897–1985); Brush and watercolor, silver paint, graphite on paper; (58.2 x 37 cm (22 15/16 x 14 9/16 in.); Gift of Charles LeMaire, 1970-55-1. (right) Drawing, Costume Design: Carnation Girls, Midnight Frolic, for Ziegfeld Follies, 1921; Designed by Charles LeMaire (American, 1897–1985); Brush and watercolor, crayon, graphite on paper; 58.3 x 37.8 cm (22 15/16 x 14 7/8 in.); Gift of Charles LeMaire, 1970-55-2

Sources

“Chinese Comedy On Hewitt Stage.” New York Times, April 21, 1909.

“Hewitt Costume Party: One of the Most Novel and Amusing Events of the Years.” New York Times, April 6, 1899.

“Hewitts Give Plays in Private Theatre.” New York Times, February 26, 1908.

Kennedy, Matthew J. “Raising the Curtain: Theatrical Design in the Collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.” Objective: Journal of the History of Design and Curatorial Studies, Parsons School of Design. No. 3, Spring/Summer 2017.

One thought on “Cooper Hewitt Short Stories: Spotlight on Theater”

Jackie hewitt on January 18, 2018 at 7:04 pm

My daughter, Eleanor Hewitt is a ballet dancer and loves to perform. What a coincidence 😊