Herbert Bayer is known for his work as a student and teacher at the Bauhaus, the famous German art school that integrated art, design, and daily life. During Bayer’s formative years at the Bauhaus (1921–1928), he helped create the modern discipline of graphic design by using photography, type, and geometric systems to promote products and ideas.

After leaving the Bauhaus, Bayer continued his career for over five decades. A pioneer in the field of information design, he produced advertisements, pamphlets, magazine layouts, and books explaining complex scientific concepts. He was especially fascinated by bodily mechanisms, from the human eyeball to the female uterus. He created a brochure called “The Menstrual Cycle” shortly after emigrating to the U.S. in 1938. At the time, pharmaceutical companies were beginning to commission modern graphic designers to create sophisticated marketing materials. This brochure, illustrating the cycle of a woman’s period, promoted hormone-based drugs to doctors, who would then prescribe these medications to treat menstrual discomfort and irregularity. To create the artwork for this brochure, Bayer painted the illustrations with gouache. The black background evokes the night sky, and tiny moons in each corner compare the female cycle to the lunar orbit. Thin lines radiate from the center of the womb, counting out the twenty-eight days of the menstrual cycle.

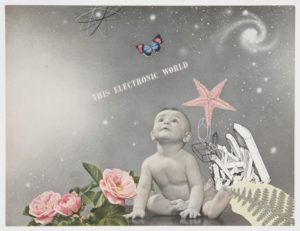

Booklet, Electronics—A New Science for a New World, 1942; Designed by Herbert Bayer; Client: General Electric Company; Offset lithograph; 21.1 × 27.7 cm (8 5/16 × 10 7/8 in.); Collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Museum purchase through gift of the Taub Foundation, 2016-54-273. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Science, marketing, and metaphor mingle in many of Bayer’s beautifully rendered graphics. While the menstrual brochure delves deep into a biological process, other pieces depict fantastic, utopian scenes of technological progress. In a photo illustration from a 1942 brochure for General Electric, a baby stares at a sky studded with natural wonders—from a colorful butterfly and a pink starfish to a swirling galaxy and a spinning atom. To create this seamless view of a future enhanced by electronics, Bayer assembled photographs, scientific engravings, and hand-painted illustrations.

Bayer had begun to create photomontages at the Bauhaus, inspired by the work of his Bauhaus colleague László Moholy-Nagy. He super-charged his technique in the 1930s by adding illusionistic layers of full-color illustration to black-and-white photographs. He cut and pasted photographic prints and then worked on top of this montage base to add color and detail. He used gouache as well as airbrush, a device that sprays a fine gradient of paint on a surface. Airbrush, which leaves no evidence of the artist’s hand, was widely used for retouching photographs in the pre-digital era. The finished artwork would then be photographed for reproduction. Bayer later wrote, “the once static viewpoint…gave way to a dynamic ‘multi-point-of-view’ to which montage lends itself naturally. In this view the painter looks at the subject from all sides. Simultaneously, he looks through it, he gets into the midst of it, adding a super real dimension.”[i] Bayer’s photo-illustrations bring us deep inside the human body and carry us out into the heavens, offering visions and viewpoints that couldn’t otherwise be grasped.

Bayer’s works are on view at Cooper Hewitt in the exhibition Herbert Bayer: Bauhaus Master, through April 5, 2020.

[i] Herbert Bayer, “statement about fotomontages (1975),” in Arthur A. Cohen, Herbert Bayer: The Complete Work (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1984), 363–4.

Ellen Lupton is Senior Curator of Contemporary Design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum and the author of numerous publications, including Design Is Storytelling, The Senses: Design Beyond Vision, and How Posters Work.