Tennessee Williams (1911–1983) wrote some of the most memorable narratives of his time. His plays and short stories explore sexual shame, grief, and power. Queer love often appears as a site of anguish and secrecy while straight sex often functions as a weapon of violence and self-destruction—especially against women. Alvin Lustig (American, 1915–1955) and Elaine Lustig Cohen (American, 1927–2016) designed covers for many works by Williams, published by New Directions Books. These iconic book covers employ type and image to build an emotional setting for the text.

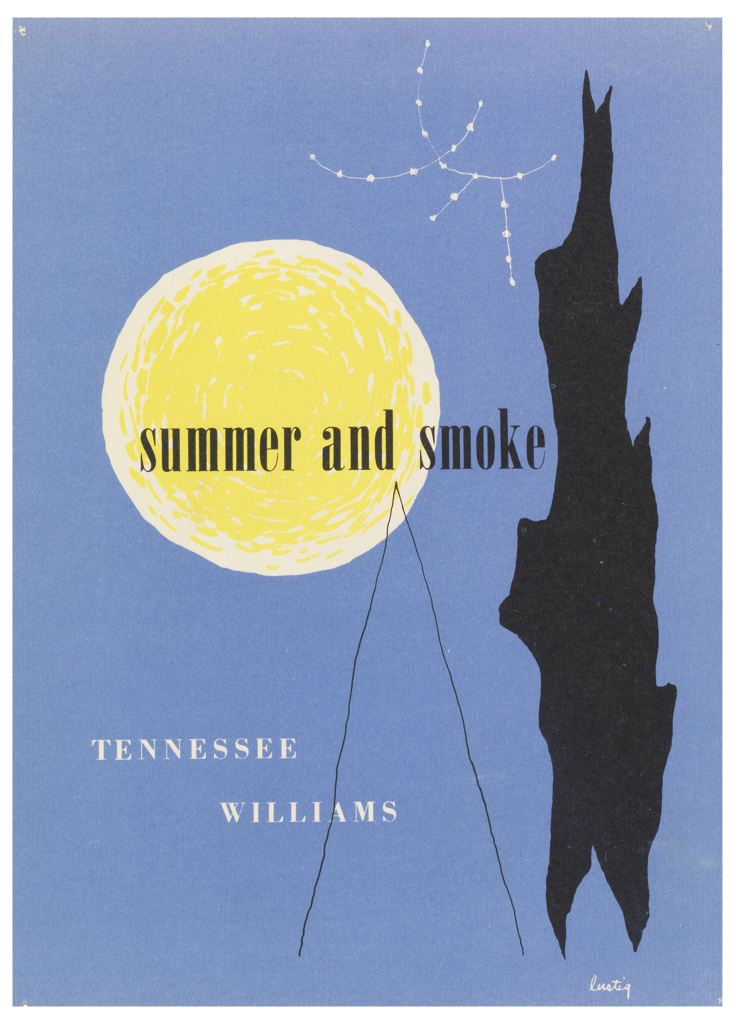

Book Cover, Summer and Smoke by Tennessee Williams, 1948; Designed by Alvin Lustig (American, 1915–1955) for New Directions Books (New York, New York, USA); Lithograph on laid paper; H × W: 21.0 × 15.2 cm (8 1/4 × 6 in.); Gift of Susan Lustig Peck, 2001-29-26

Lustig’s cover design for Summer and Smoke (1948) portrays a yellow moon, black flame, and a deep blue sky. In the play, a virtuous young woman in a Mississippi town resists the sexual advances of a cherished friend—but when she changes her mind later, he rejects her. In despair, she leaps into a casual encounter with a traveling salesman. Sex is obliterating, not liberating.

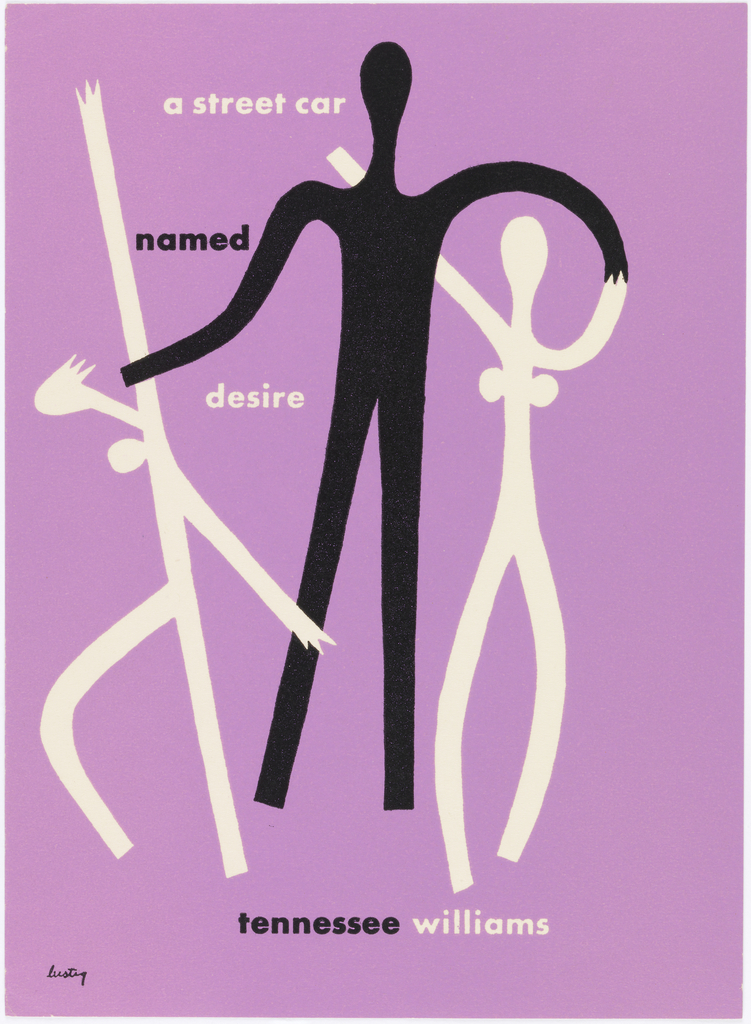

Book Cover, A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams, 1947; Designed by Alvin Lustig (American, 1915–1955) for New Directions Books (New York, New York, USA); Lithograph on paper; H × W: 23.5 × 17.1 cm (9 1/4 × 6 3/4 in.); Gift of Susan Lustig Peck, 2001-29-28

Lustig designed dozens of abstract covers for New Directions Books in the 1940s and ‘50s. He and other artists—including Andy Warhol and Ray Johnson—produced bold designs for New Directions’s reprints of modern classics and original works. His cover for the first edition of A Streetcar Named Desire, alongside the play’s 1947 theatrical debut that electrified the American theater, shows a black, wiry abstraction of a human figure dominating two smaller figures, drawn in white. In the play, Stanley Kowalski commits physical and psychological violence against his wife, Stella, and her sister, Blanche DuBois, a disgraced Southern belle. The three characters live together in a cramped New Orleans apartment as Stella attempts to support Blanche who is in a precarious state of mental health. Blanche’s husband had killed himself after she discovered him having sex with another man and shamed him for this transgression. Blanche collapses mentally at the end of the play after Stanley rapes her. Streetcar, Williams’s most popular and well-known play, became a film in 1951.

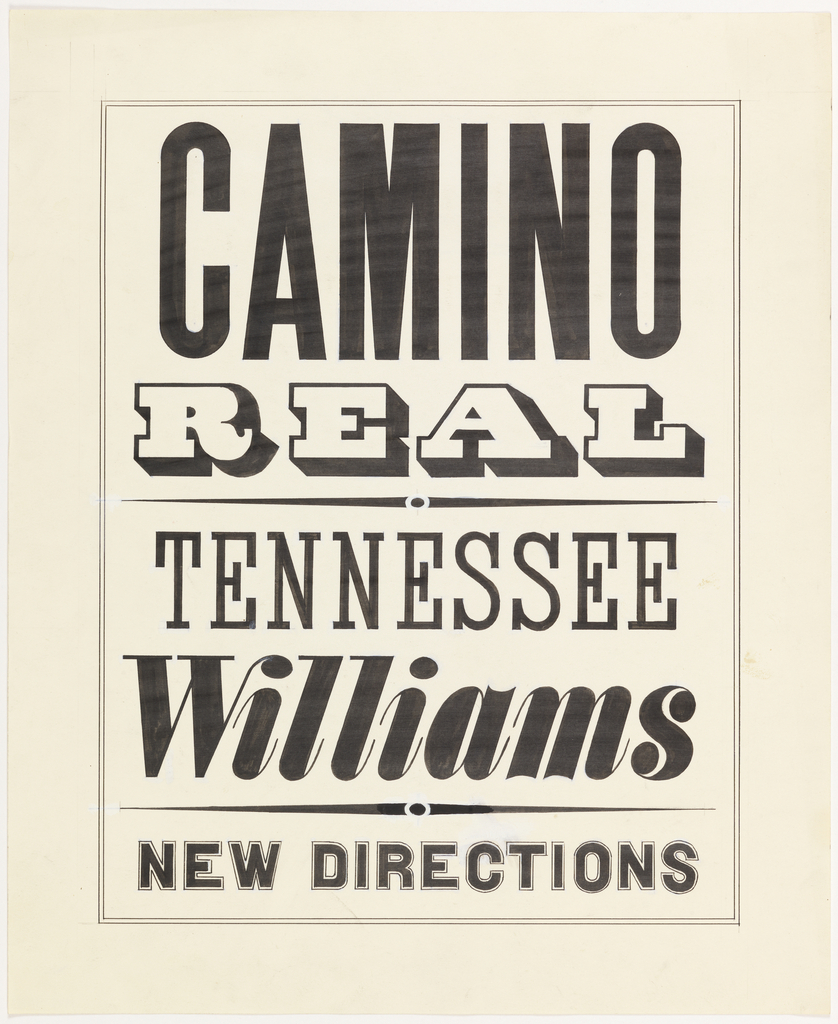

Book Jacket Design, Camino Real by Tennessee Williams, 1953; Designed by Alvin Lustig (American, 1915–1955) for New Directions Books (New York, New York, USA); Felt tip pen and black ink on off-white wove paper; H × W: 34.5 × 28.4 cm (13 9/16 × 11 3/16 in.); Gift of Tamar Cohen and Dave Slatoff, 1993-31-153

Other works by Williams explore the perils of non-heterosexual identity in an unaccepting society. Camino Real (1953) explores the exploits of an openly gay outlaw who is ultimately killed by the police. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955) is about a man struggling with the suicide of a gay friend (and possibly former romantic interest), who killed himself after the hero rejects him sexually. Williams wrote these works against a backdrop of oppression and hate. For much of his life, Williams veiled his sexual identity as a gay man. It was an open secret, cloaked in innuendo. He came out publicly in 1970, shortly after the Stonewall uprising that galvanized the modern gay rights movement in the United States.[i] But in the 1950s, the toxic witch hunts of Senator Joe McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee in the US House of Representatives blacklisted gay and lesbian actors and writers, forcing them deeper into the closet. In many states, anti-sodomy laws made queer love a crime, while psychiatric manuals categorized homosexuality as a mental illness. Hollywood’s official code of decency forbade the direct depiction of any sexual activity judged to be a perversion.[ii]

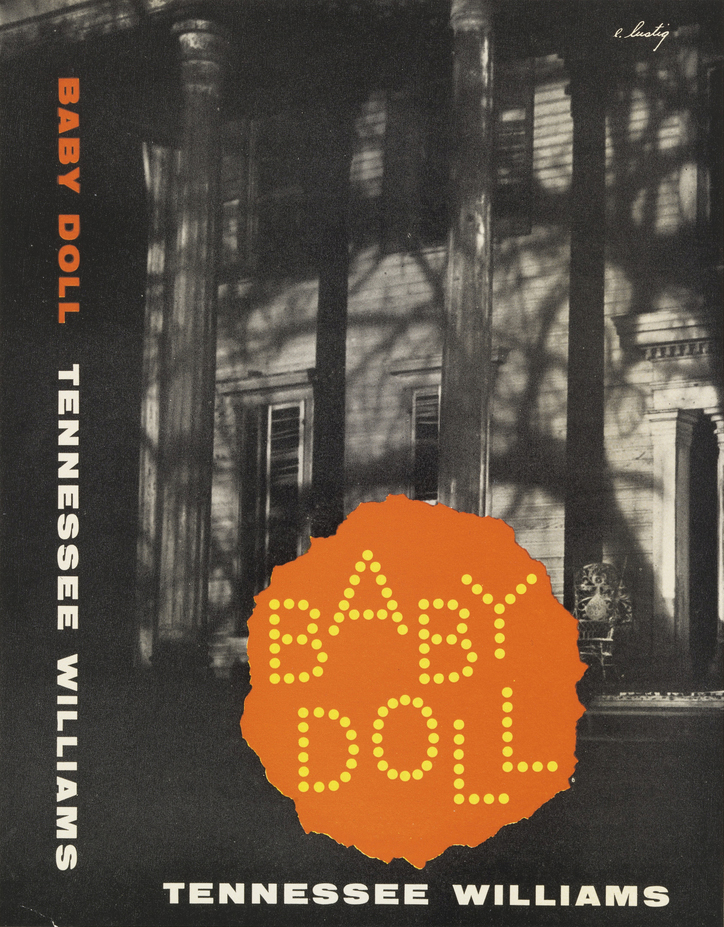

Book Cover, Baby Doll by Tennessee Williams, 1957; Designed by Elaine Lustig Cohen (American, 1927–2016) for New Directions Books (New York, New York, USA); Offset lithograph on paper; H × W: 20.9 × 22.3 cm (8 1/4 × 8 3/4 in.); Gift of Tamar Cohen and Dave Slatoff, 1993-31-47

Lustig’s wife, Elaine Lustig (later Elaine Lustig Cohen), worked with him in his studio and assumed growing responsibility as diabetes attacked his eyesight. After Alvin Lustig’s death at age 40 in 1955, Elaine Lustig continued the studio’s work on her own. She designed covers for several works by Williams, including Baby Doll (1956). The title character is a teenage bride trapped in an oppressive marriage; she commits adultery and gets away with it, experiencing a sexual awakening. The film triggered national outrage—Hollywood’s code insisted that acts of adultery be punished, not forgiven. Baby Doll also gave ladies’ sleepwear a freshly named category: the baby doll nightie, worn by the story’s heroine as she naps in her adult-sized crib. Lustig Cohen’s cover interprets the story’s weird collision of childlike and adult behaviors with a moody photograph of a Southern mansion superimposed by bright, polka-dot typography.

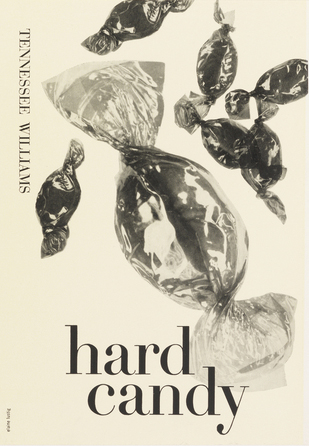

Book Cover, Hard Candy by Tennessee Williams, 1954; Designed by Elaine Lustig Cohen (American, 1927–2016) for New Directions Books (New York, New York, USA); Offset lithograph on glossy paper; H × W: 22.2 × 50.3 cm (8 3/4 × 19 13/16 in.); Gift of Tamar Cohen and Dave Slatoff, 1993-31-53

For the 1959 edition of Hard Candy, a collection of short stories, Lustig Cohen photographed cellophane-wrapped sweets and printed them at a large scale in black and white. Her bleak cover design undercuts any charming or sentimental reading of the book’s title. Lustig Cohen’s cover is still in print by New Directions Books. In the title story, an elderly man travels by bus several times a week to a cinema at the edge of town, where he pays for sex with candy and quarters. At the end of the story, the man is found dead in the theater, on his knees, surrounded by candy wrappers.

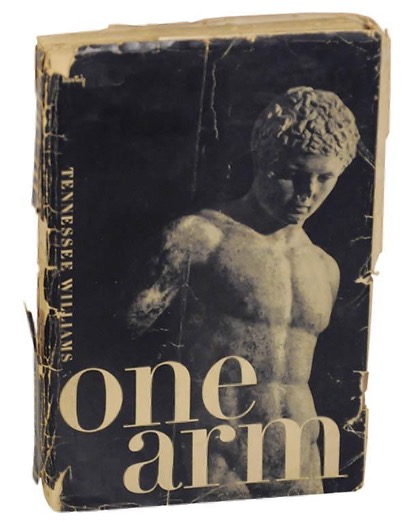

Williams’s pictures of gay life were not heroic or uplifting. Nor were his pictures of heterosexual life. He used poetry, satire, and wit to shine slivers of light onto his dark portraits of people and places. Lustig and Lustig Cohen’s designs for his work reinforce this disquieting tension of existence and terror. Filmmaker and queer icon John Waters wrote in 2006, “Tennessee Williams saved my life.” As a child growing up in Baltimore, Maryland, Waters yearned for the “bad influences” that society was trying to hide from him. Williams’s book One Arm (1950) was sequestered on an adults-only shelf in the public library; Waters stole this forbidden literary fruit and discovered a new world of real people in dreadful situations. (The title story is about a gay man and former boxing champ who lost his arm in a car crash.) Waters embraced Williams as a personal idol who was “joyous, alarming, sexually confusing, and dangerously funny.”[iii] Tennessee Williams was all those things, even as he depicted low points in the human condition.

Book, One Arm by Tennessee Williams, 1950; Designed by Alvin Lustig (American, 1915–1955); Photo: Jeff Hirsch Books

Ellen Lupton is Senior Curator of Contemporary Design at Cooper Hewitt.

Notes

[i] Annette J. Saddik (moderator), David Savran, Michael Paller, Dirk Gindt, “Out of the Closet, Onto the Page: A Discussion of Williams’s Public Coming Out on The David Frost Show in 1970 and His Confessional Writing of the ‘70s,” Tennessee Williams Scholars Conference, March 24, 2010, http://www.tennesseewilliamsstudies.org/journal/work.php?ID=111.

[ii] Dean Shackelford, “The Truth That Must Be Told: Gay Subjectivity, Homophobia, and Social History in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” The Tennessee Williams Annual Review, No. 1 (1998), pp. 103–18.

[iii] John Waters, “The Kindness of Strangers,” The New York Times, November 19, 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/19/books/review/Waters.t.html.