Written by Ellen Lupton with Matthew Kennedy

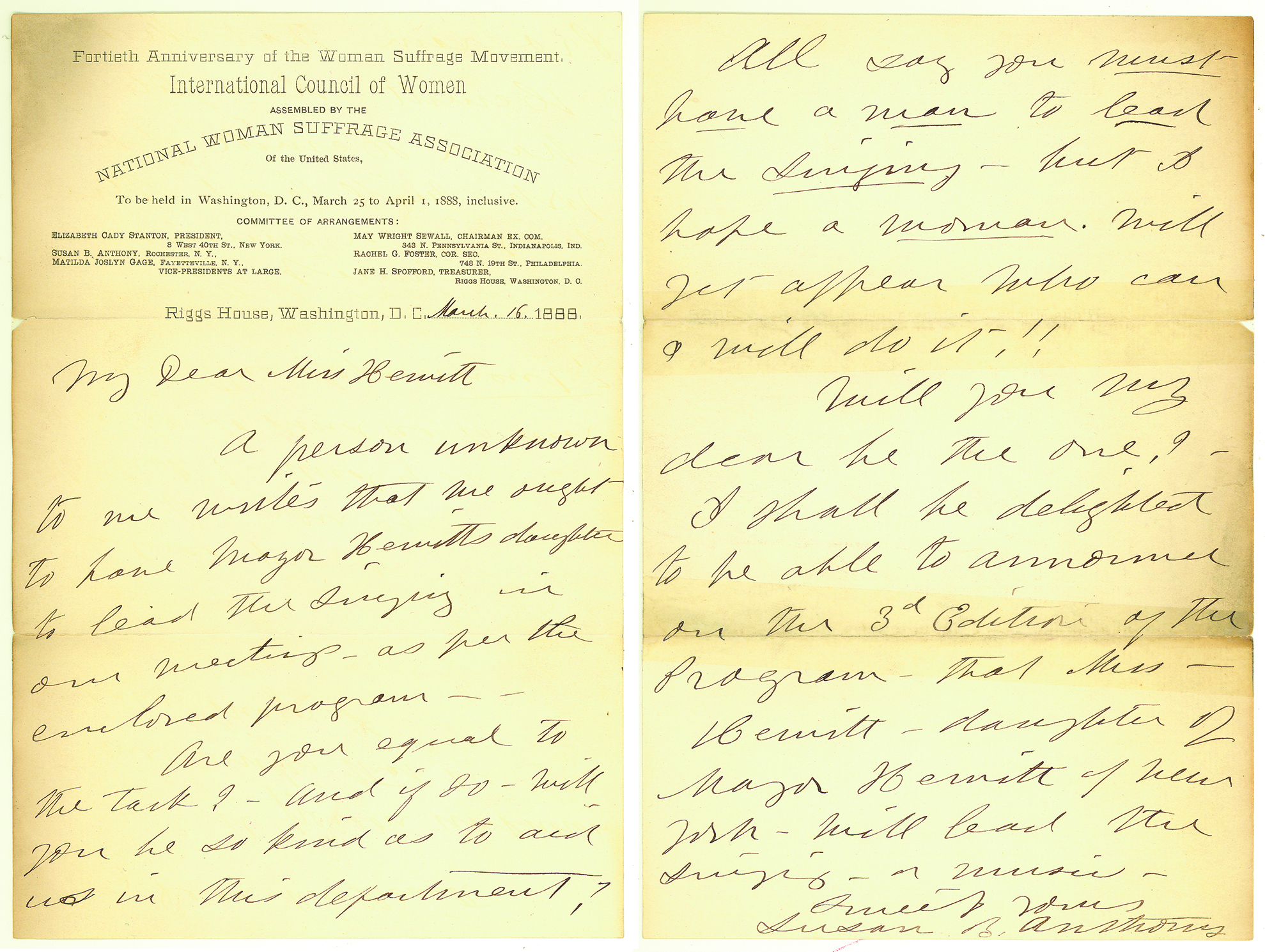

Letter from Susan B. Anthony to one of the Hewitts, 1888. Courtesy of The Cooper Union Archive and Special Collections.

In 1888, Susan B. Anthony invited one of the Hewitt sisters—Sarah or Eleanor, daughters of New York City mayor Abram Hewitt—to lead the singing at an upcoming meeting of the National Woman Suffrage Association. Anthony wrote, “I shall be delighted to be able to announce on the 3rd edition of the program that Miss Hewitt—daughter of Mayor Hewitt of New York—will lead the singing or the music.” At the time, such ceremonial honors were limited to men, but Anthony hoped that a “woman will yet appear who can and will do it!!”

Miss Hewitt probably declined the invitation. The Hewitt family was opposed to granting women the right to vote. Abram Hewitt’s own treatise against women’s suffrage, published in 1894, repeated the anti-suffrage movement’s core beliefs. He argued that voting would expose women to future dangers, such as holding public office or serving in the military, and it would sully feminine virtue with the corruption of party politics. Hewitt said that women should reform society from inside the home—not outside in the public square. First and foremost, restricting the right to vote kept men manly and ladies ladylike, preserving what he and many others believed were fundamental differences between males and females. In Hewitt’s words, universal suffrage would cause the “unsexing of men and women” by destroying the “sanctity and privacy” of the home. Suffrage threatened the gendered order of family, work, and government.[i]

In 1895, the first meeting of the New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage was hosted in the home of Abram Hewitt and his wife Sarah Amelia Cooper Hewitt. The group fought women’s suffrage in New York State. (The suffrage movement was initially contested on a state-by-state basis.) According to historian Susan Goodier, Sarah Amelia supported the group but was not an outspoken member. In 1906, Eleanor was listed as a member of the Standing Committee, joining a long roster of prominent women. In 1917, Sarah and Eleanor hosted an “Anti-Suffrage Review” in their home; at this point, the movement was losing steam, and the New York State Constitution affirmed women’s right to vote that year.[ii]

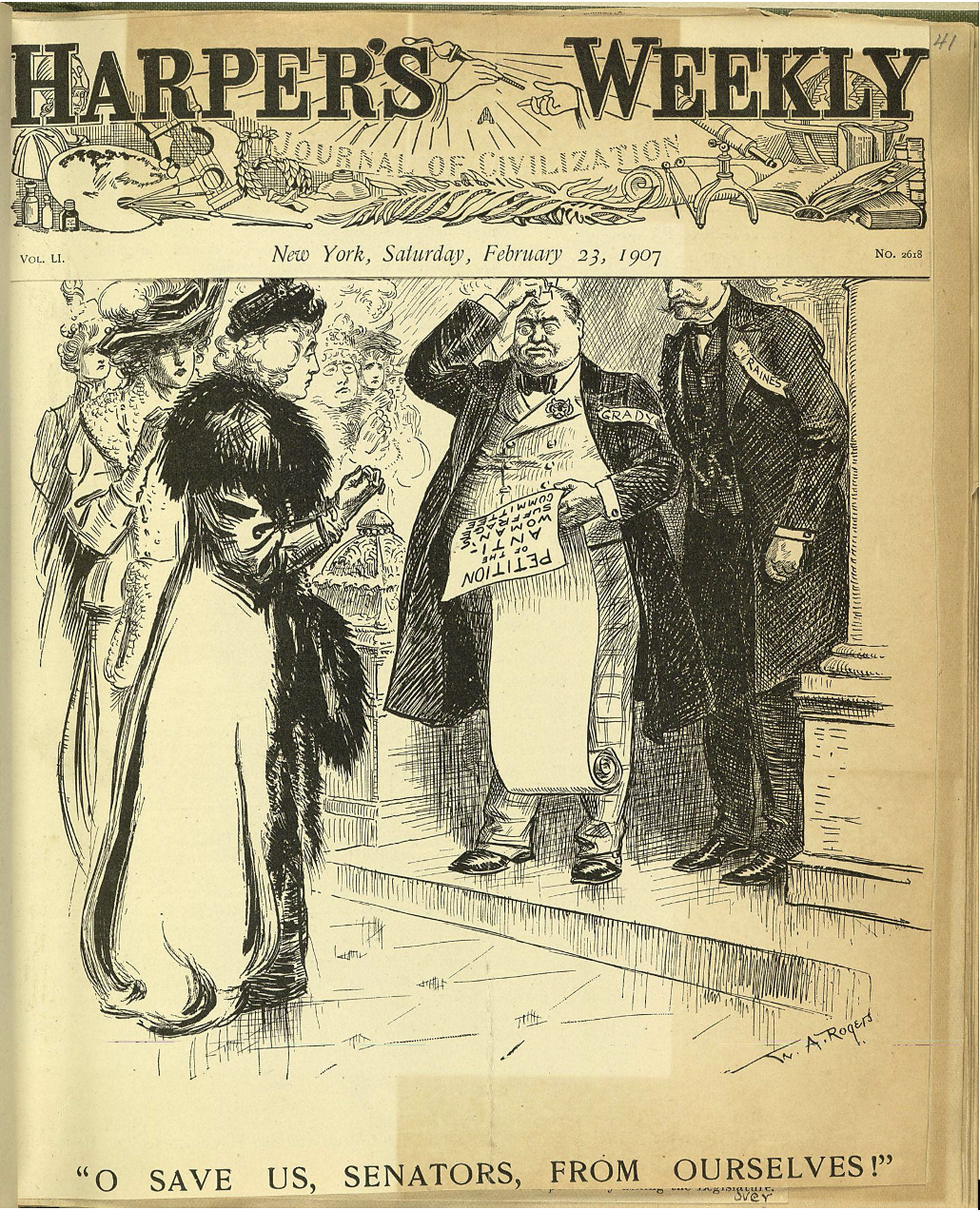

Especially in the state of New York, many influential anti-suffragists were women. Calling themselves “antis,” these women defended their own right NOT to vote. The antis claimed that most women embraced the values of home, family, and feminine virtue enshrined by the status quo. Protected by wealth and social privilege, most anti-suffrage leaders were the daughters or wives of bankers, lawyers, businessmen, or political leaders. The presence of anti-suffrage women at pro-suffrage hearings caught the eye of the press, who gleefully noted the irony in groups of women asking male legislators to keep them disenfranchised.

W. A. Rogers, Harper’s Weekly cover, “O Save Us, Senators, from Ourselves!” February 23, 1907. In this cartoon, New York Senator Thomas Grady is scratching his head over a petition handed to him by a well-dressed anti-suffragist.

One of Sarah and Eleanor’s best friends was writer and editor Caroline King Duer. While Duer’s individual view on the issue of women’s suffrage is not explicitly known, she was raised in a “liberated” family and was possibly pro-suffrage like her sisters, author Alice Miller and suffragist Katherine Mackay.[iii] Mackay founded the Equal Franchise Society, which encouraged wealthy women to consider suffrage and promoted dialogue with antis. Miller contributed extensive writing to the pro-suffrage movement, often questioning how women’s humanity is valued if their voices are not to be heard publicly. Her series of satirical poems in the New York Tribune was subsequently published in 1915 as the book Are Women People?. (She published her triumphantly titled follow up Women Are People! in 1917.)

Alice Duer Miller, Are Women People?: A Book of Rhymes for Suffrage Times. New York: George H. Doran Company, 1915. National American Woman Suffrage Association Collection, Library of Congress.

Anti-suffrage paraphernalia in volume III (1902–32) of the Ringwood Manor guestbooks. Courtesy of Ringwood Manor.

Meanwhile, two pieces of paraphernalia that encourage a “no” vote on women’s suffrage can be found affixed to a page in a volume of the guestbooks from Ringwood Manor, the Hewitt family’s country estate in New Jersey, dated around 1915. Women’s suffrage in New York State was defeated by a strong majority in a 1915 referendum but was signed into law two years later. (As depicted on the stamp, red flowers were symbols of the anti-suffrage movement, contrasting vibrantly with the white garments and yellow roses worn by advocates for voting rights.) While a flurry of signatures floats above these pieces and on preceding and following pages of the guestbook, it is not directly evident who may have put them there, nor what debate may have ensued amongst the Hewitts and their guests on both sides of the issue.

Many anti-suffragists fought for multiple causes. Although the anti-suffragists had reactionary views of voting rights, many of these women forged new institutions that aimed to improve women’s lives. Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt founded the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration (now Cooper Hewitt) with a goal of enhancing women’s education and their opportunities for employment. Education, not political activism, was central to their work. Likewise, many anti-suffragist women were innovators, reformers, and philanthropists. Annie Nathan Meyer helped found Barnard College. (Abram Hewitt was also a founding member and chairman of Barnard’s board.) Anna C. Maxwell ran a school for nurses. Josephine Jewell Dodge established nursery programs for the children of poor and working families.[iv] The antis distrusted party politics and doubted that voting would eliminate such problems as rampant alcohol abuse, which many suffragists hoped to solve by extending the vote to wives and mothers.

Goodier argues that the persistent visibility of the antis forced suffragists to adopt (and redirect) the central claim of the antis: that men and women are separated by fundamental virtues and abilities. Weaponizing the myth of women’s unique moral qualities, the suffragists argued that the woman’s vote would help cleanse politics of deceit and corruption. They used the stereotypical, gender-normative notion that women are more virtuous than men to carry women’s suffrage to victory, paving the way for more gender equality. Three decades after Anthony’s letter to one of the Hewitt sisters, the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified by the necessary 36 states and became national law.

Ellen Lupton is curator emerita after 30 years at Cooper Hewitt as a curator of contemporary design. Matthew Kennedy is the Publications Associate and assisted in organizing the exhibition Sarah & Eleanor Hewitt: Designing a Modern Museum on view through October 23, 2022.

Notes

[i] Hewitt, Abram S. (Abram Stevens), “Circular : Statement in regard to the suffrage / by the Hon. Abram S. Hewitt. 1894,” Ann Lewis Women’s Suffrage Collection, accessed February 2, 2022, https://lewissuffragecollection.omeka.net/items/show/1518.

[ii] Susan Goodier, No Votes for Women: The New York State Anti-Suffrage Movement (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2013). The group was later called the New York State Association Opposed to the Extension of the Suffrage. Eleanor’s name appears in New York State Association Opposed to the Extension of the Suffrage to Women Eleventh Annual Report, New York City, New York, December 1906, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbcmil.scrp3001801/?sp=3.

[iii] Alfred Allan Lewis, Ladies and Not-So-Gentle Women: Elisabeth Marbury, Anne Morgan, Elsie de Wolfe, Anne Vanderbilt, and Their Times (New York: Penguin Books: 2000), 85.

[iv] Linton Weeks, “American Women Who Were Anti-Suffragettes,” NPR, October 22, 2015, https://www.npr.org/sections/npr-history-dept/2015/10/22/450221328/american-women-who-were-anti-suffragettes.