Written by Dr. Sue Perks

In conjunction with the exhibition Give Me a Sign: The Language of Symbols, designer and researcher Sue Perks offers an expansive look into the Henry Dreyfuss Archive held at Cooper Hewitt. The archive contains detailed documentation on Dreyfuss’s Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, which serves as the basis for the exhibition.

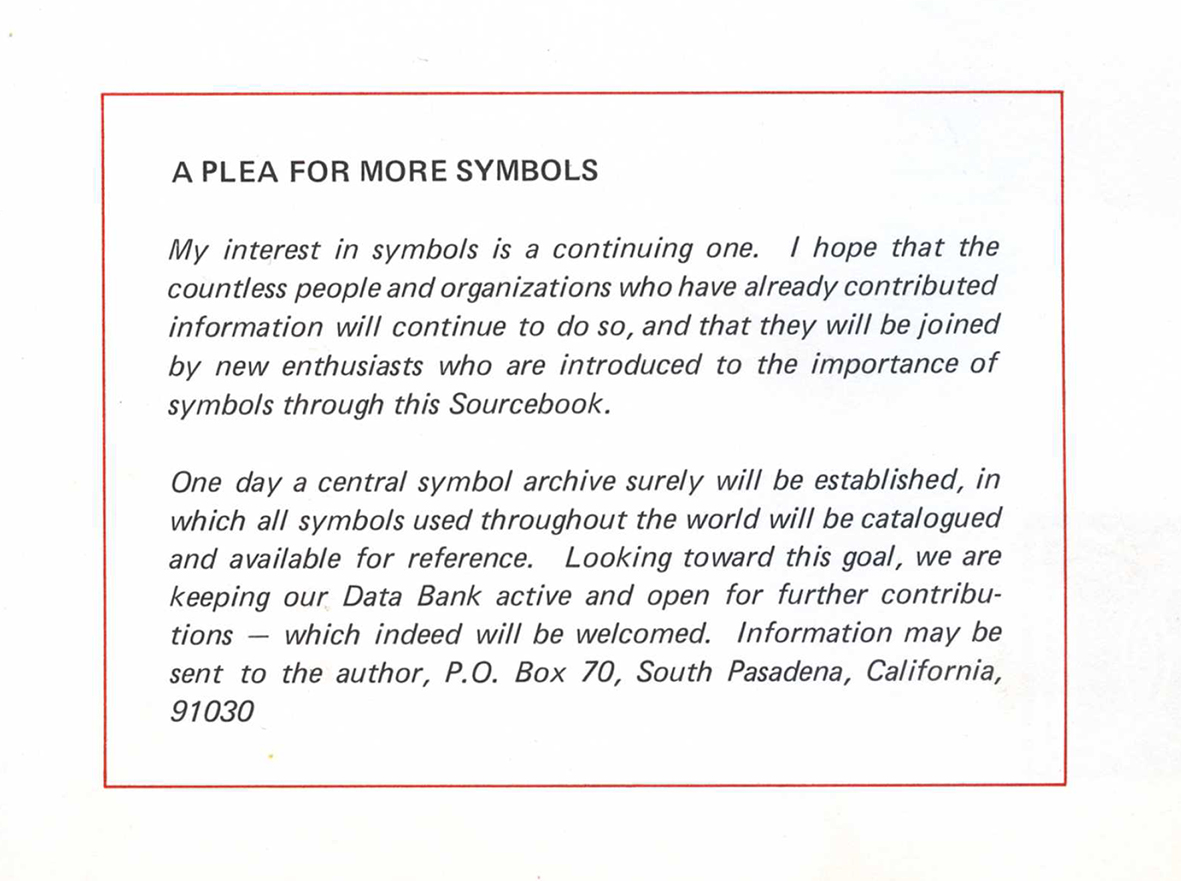

The Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Symbols is just that: It’s not an inclusive dictionary of all symbols but does represent a state-of-the-art collection of the most important symbols it was possible to collect and classify in the early 1970s. It represents the culmination of Henry Dreyfuss’s work with symbols, which he had been expanding and developing for decades and had finally managed to fund and complete. The 3,000+ symbols (many duplicated throughout the sections) are sourced from Dreyfuss’s symbol Data Bank, which numbered some 20,000 symbols by 1972. The book itself was eagerly anticipated by symbol enthusiasts of the time who believed that symbols could break the language barrier and facilitate international communication. The foreword was written by prominent architect and thinker R. Buckminster Fuller, who praised Dreyfuss’s attempts to use symbols to create a more cohesive world. In the frontispiece of the first edition of the Symbol Sourcebook (published on January 11, 1972) (fig. 1), Dreyfuss asks readers to keep sending more symbols to be added to the Data Bank, which in January 1972 remained “active and open for further contributions,” with the hope of one day creating “a central symbol archive . . . in which all symbols used throughout the world will be catalogued and available for reference.”

Figure 1: “A Plea For More Symbols” by Henry Dreyfuss, Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, 1972; Henry Dreyfuss Archive, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Image © Smithsonian Institution

The Sections within the Symbol Sourcebook

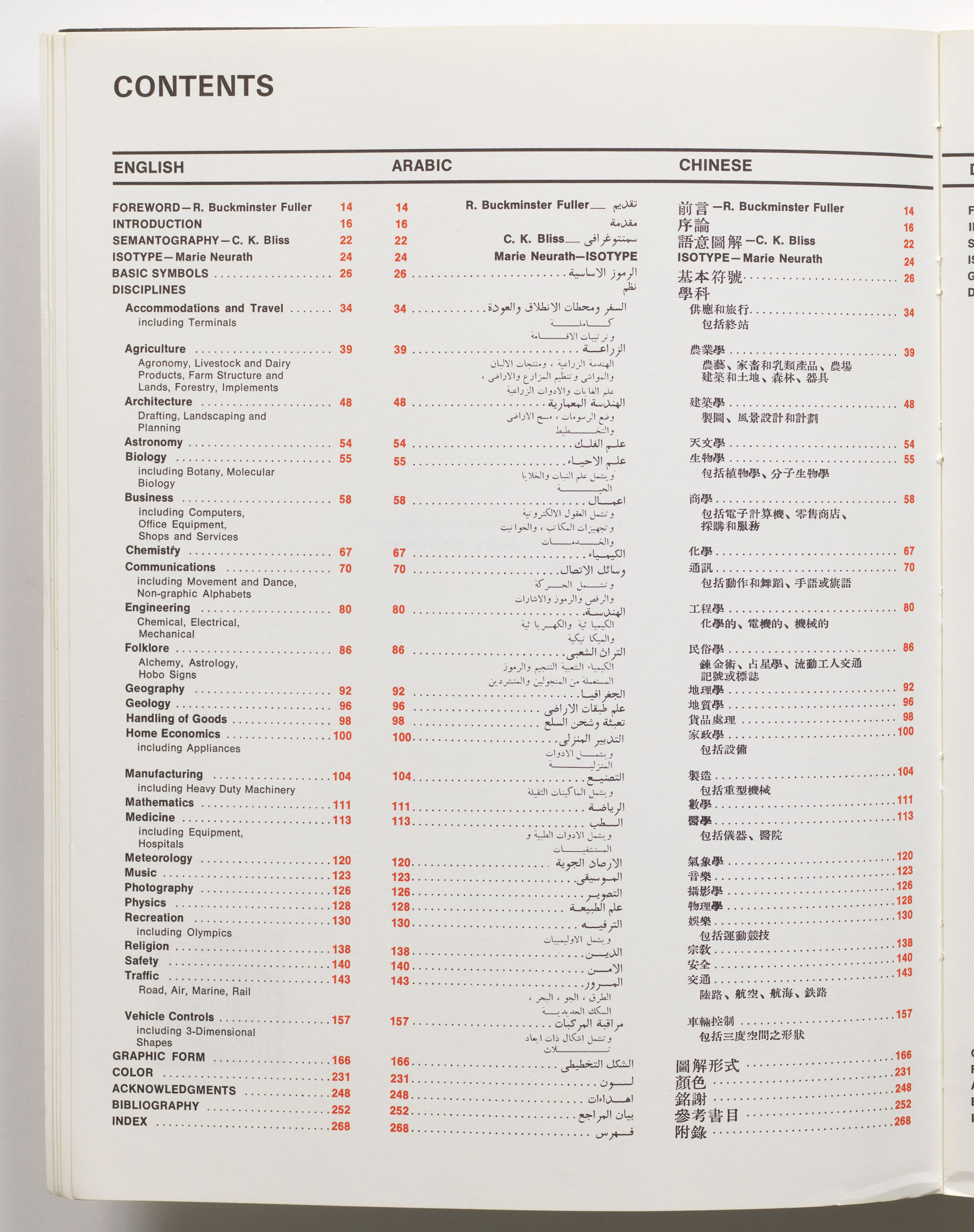

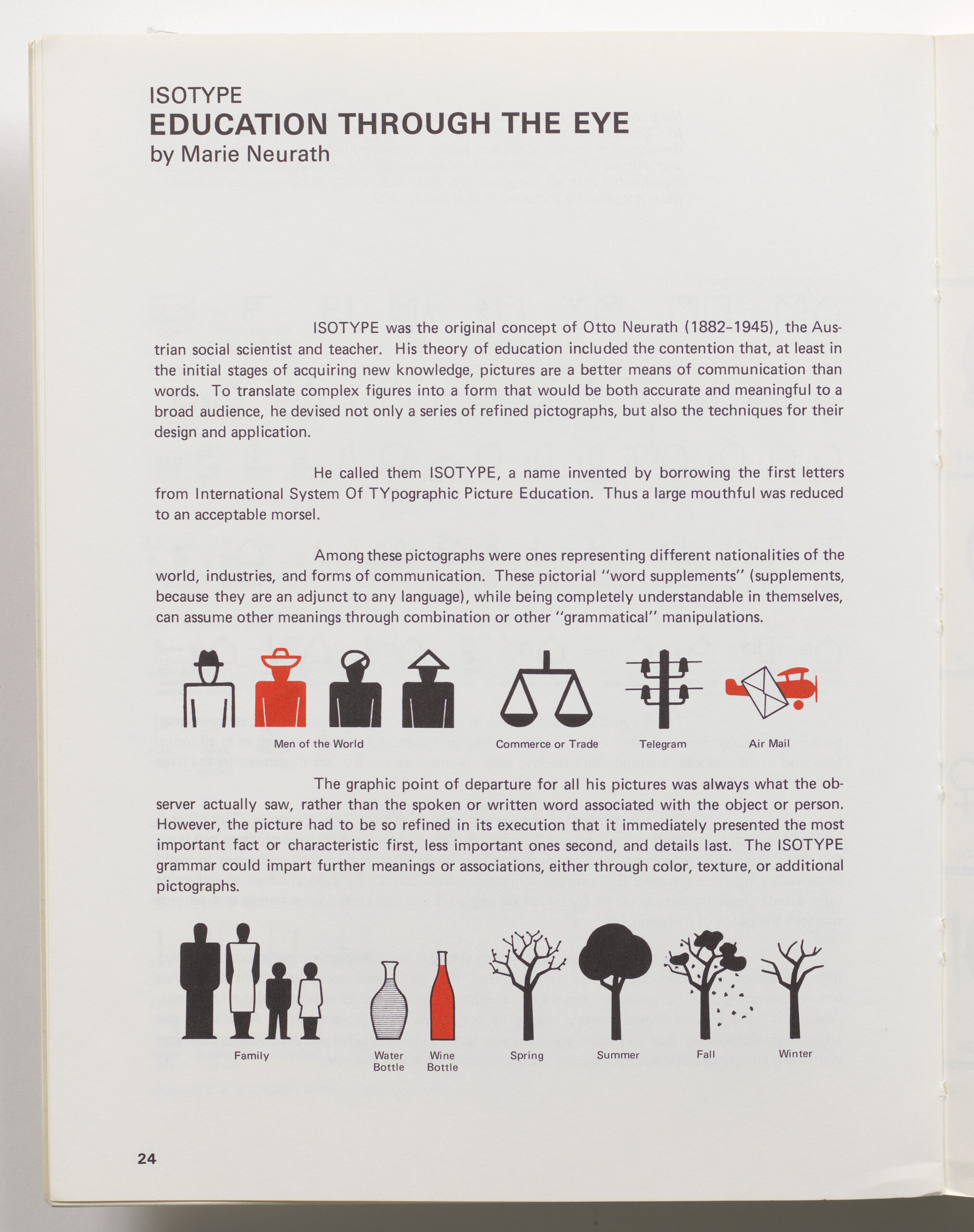

The introductory section of the book is divided into several sections: “Contents” (in 18 languages) (fig. 2); “Foreword” by R. Buckminster Fuller; and “Introduction” by Dreyfuss, which sets out his philosophy and reasons for producing the book. It then features two significant visual languages, in “Semantography” by Charles K. Bliss and “Isotype” by Marie Neurath (fig. 3). The “Basic Symbols” section leads the audience through a brief semiotic education before the main parts of the book are presented.

Figure 2: Table of Contents, Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, 1972; Henry Dreyfuss Archive, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum Design Museum; Image © Smithsonian Institution

Figure 3: “Isotype: Education Through The Eye” by Marie Neurath, Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, 1972; Henry Dreyfuss Archive, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Image © Smithsonian Institution

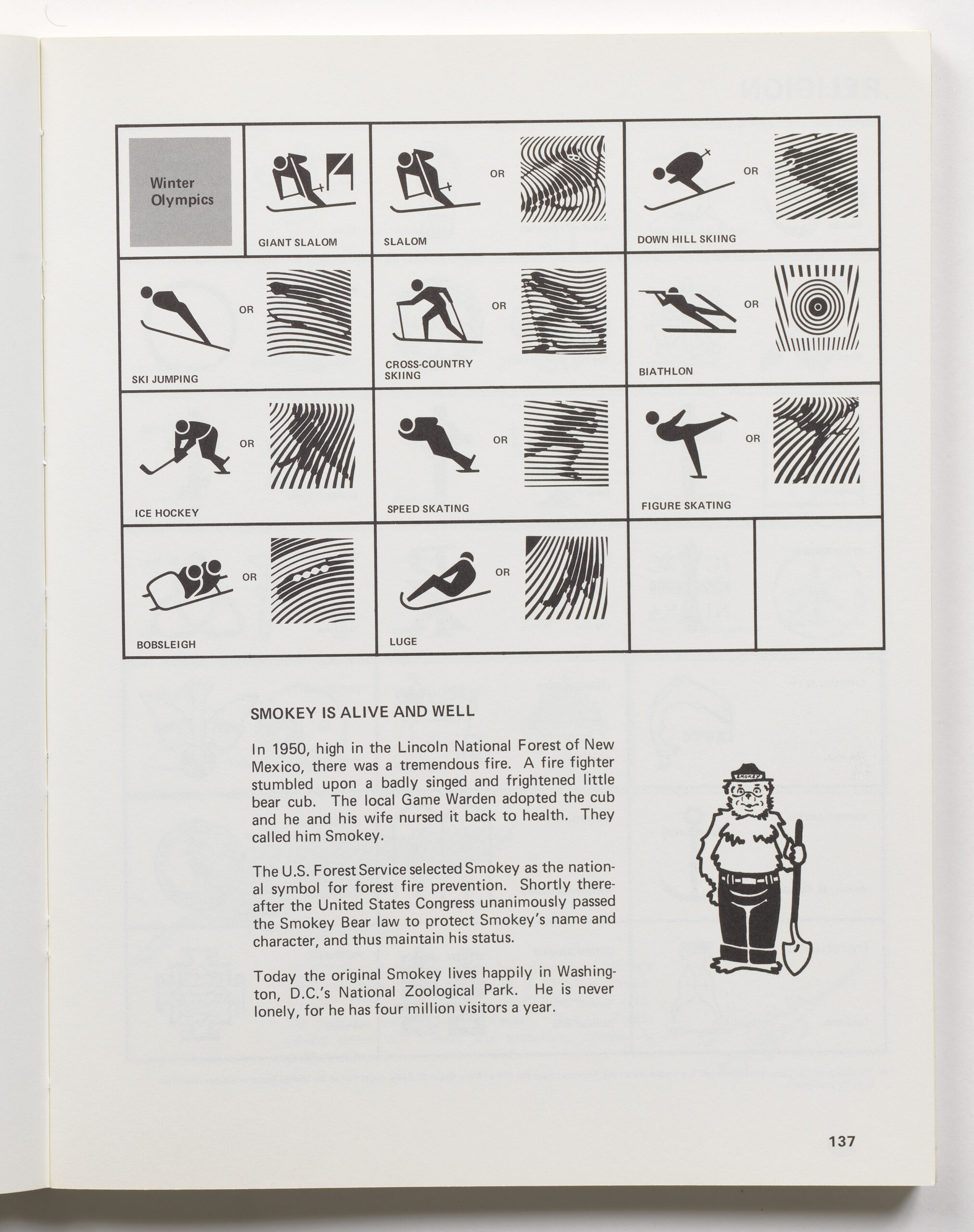

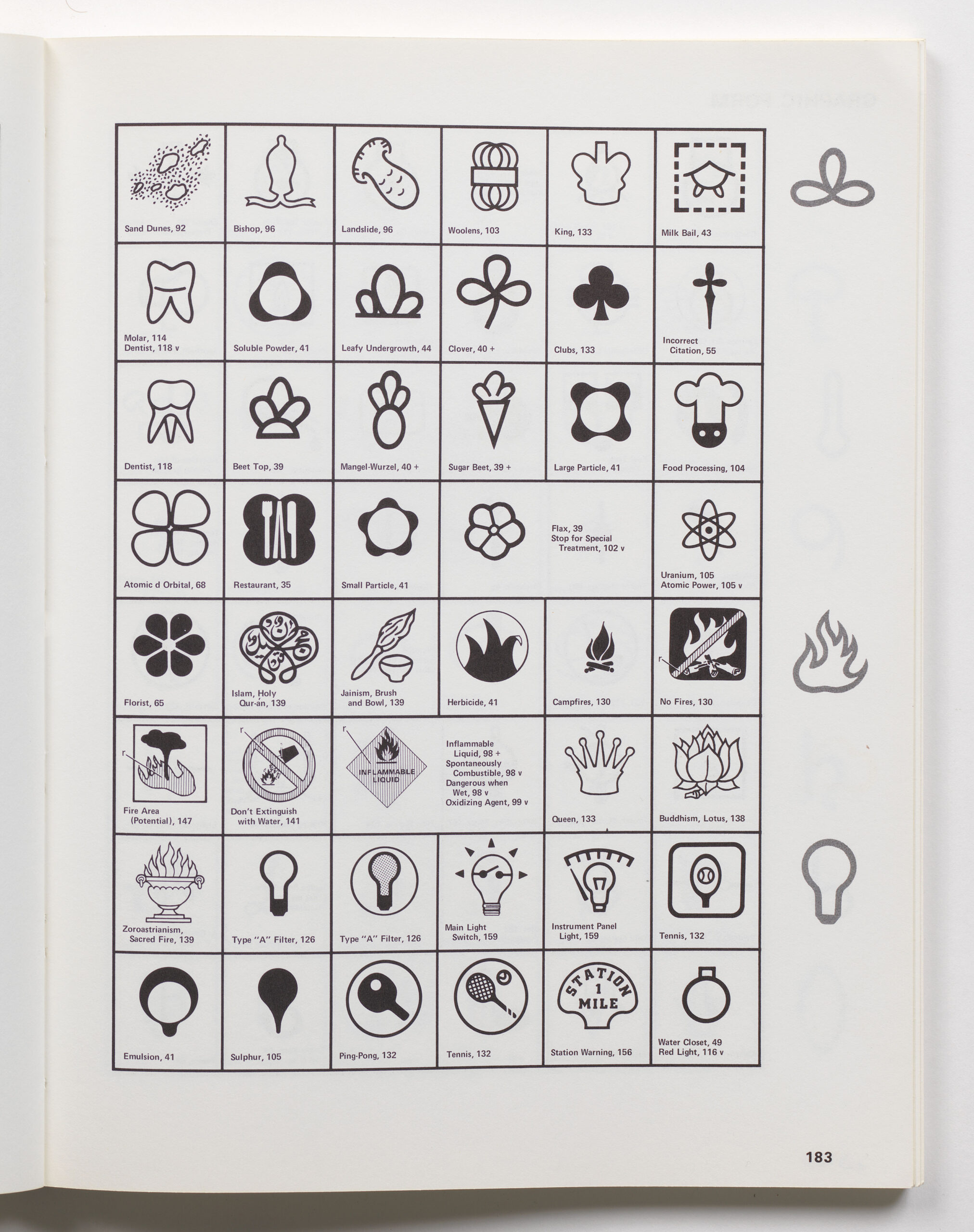

The “Disciplines” section forms one of the three main sections of the book, along with the “Graphic Form” and “Color” sections. There are 26 listed disciplines (such as Agriculture, Communications, Recreation, and Traffic) that contain up to 42 symbols per page set in boxes within a grid. The number of pages for each discipline varies from two to eight. Each discipline ends with a more lighthearted filler or anecdote. For example, Smokey Bear, the US Forest Service’s symbol for forest fire prevention, appears at the end of the Recreation section (fig. 4).

Figure 4: “Smokey Is Alive and Well” by Henry Dreyfuss, Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, 1972; Henry Dreyfuss Archive, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Image © Smithsonian Institution

The next section describes and is titled “Graphic Form” (fig. 5). Dreyfuss states that it “permits identification of symbols out of context.” Here you can find symbols taken from the “Disciplines” section classified according to shape. In the description, Dreyfuss stresses that graphic form is based on “personal judgement” and “an individual eye.” Discerning which referents were the most relevant to include required much soul-searching and consultation with the “old school” of symbol experts, such as Marie Neurath, Margaret Mead, and Rudolf Modley. Ultimately, 16 key graphic form referents were selected, including geometric shapes, crosses, lines, humans, and animals.

Figure 5: Graphic Form Section, Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, 1972; Henry Dreyfuss Archive, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Image © Smithsonian Institution

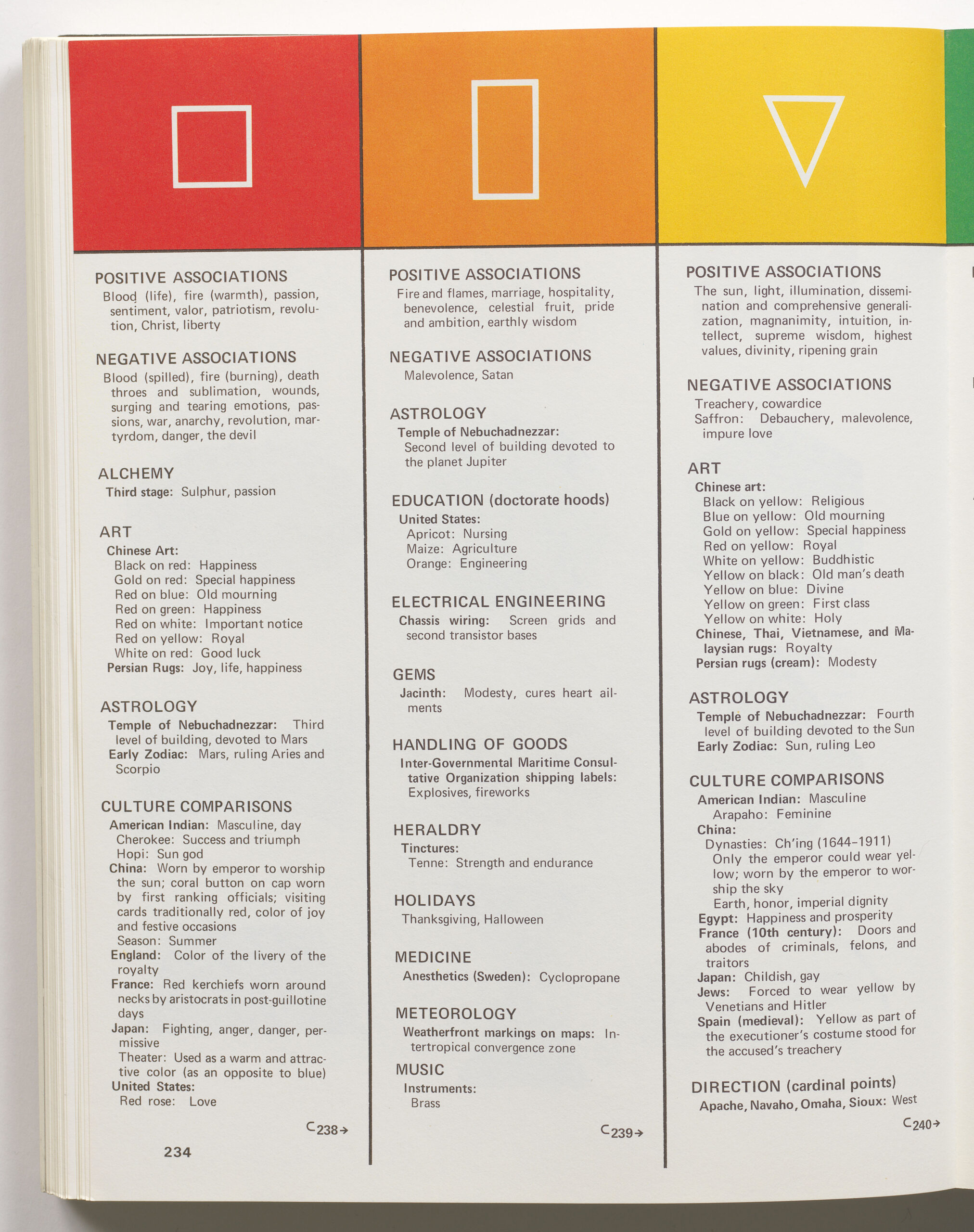

Finally, the “Color” (fig. 6) section shows how color changes the meaning of symbols. Dreyfuss acknowledges the work of color theorist Faber Birren and of artist Wassily Kandinsky and describes in detail how color plays a crucial role in the way a message is conveyed, bringing together shape, form, and discipline. Once again, Dreyfuss (with real humility) emphasizes that this classification of color is as comprehensive as possible given the time span of the book’s development and space available in the book—but notes that the subject of color is far too complex to be all-inclusive in the volume.

Figure 6: Color Section, Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, 1972; Henry Dreyfuss Archive, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Image © Smithsonian Institution

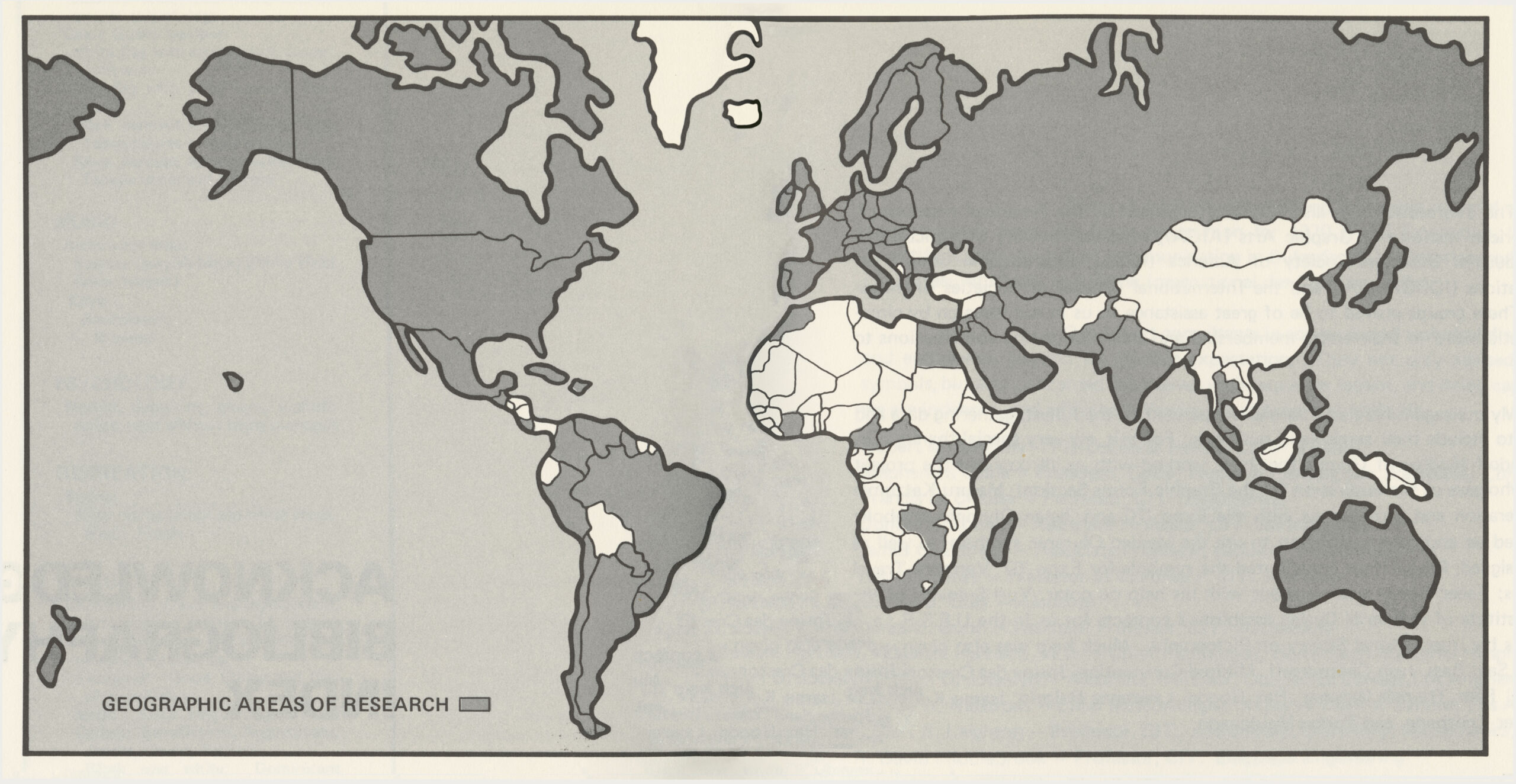

The Symbol Sourcebook concludes with the “Acknowledgements” section, where a map shows the extent of international research that took place and states Dreyfuss’s gratitude to the cream of US society, industry, and academia (fig. 7). He also generously acknowledges his team who helped to shape and compile the book. The extensive bibliography credits the most respected and learned organizations of the time, individually for each of the 26 “Disciplines” section pages and for the “Color” section. The “Index” section explains how to use the cross-referencing system in the book and offers an alphabetical list of symbol meanings and where corresponding symbols can be found. Dreyfuss felt that to credit each designer for each individual symbol was logistically unworkable, so instead he credited the main organizations that supplied the symbols.

Figure 7: Geographic Areas of Research for the Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, 1972; Henry Dreyfuss Archive, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Image © Smithsonian Institution

The Symbol Sourcebook’s success is due partly to a clever cross-referencing system, which was in place by 1970 [1] and was designed by Dreyfuss and Paul Clifton (with help from several notable symbol consultants). Subjects are accessed through the index at the back that indicates where relevant symbols can be found in one (or several) of the 26 “Disciplines” section pages. That symbol is also listed in the “Graphic Form” section with other symbols that share similar shapes. The “Color” section brings together the “Graphic Form” and “Disciplines” sections by describing a further layer of meaning when color is added to symbol forms through specific disciplines.

Before his demise in October 1972, Dreyfuss envisaged the Symbol Sourcebook and Data Bank project being continued and updated, with new symbols added over the years. Although a second edition was published with minor updates in spring 1972 and a third edition planned for later in 1972 (with a paperback reprint issued in 1984), the project was never able to fulfill its potential as the “computerized database of symbols” that Dreyfuss imagined in 1970. Further updated editions could have formed a visual record of the changing use of symbols in society, leading toward a more universal understanding of their power in society. For us today, digital technology can make this happen!

Dr. Sue Perks is a designer, archival researcher, and writer on Isotype, museum design, and Henry Dreyfuss’s work with symbols. She was awarded a PhD from University of Reading in 2013. She regularly presents at international design conferences and co-founded The Symbol Group in 2022.

The exhibition Give Me a Sign: The Language of Symbols is on display at Cooper Hewitt through September 2, 2024.

Notes

[1] The original design from 1970 numbered approximately 800 pages and included several more disciplines.

Acknowledgments

Some funding contributed by the Design History Society Research Publication Grant.