Niels Diffrient (1928–2013)

Niels Diffrient (1928–2013)Niels Diffrient loved many things, from airplanes to ice dancing. He loved his three children and his wife Helena Hernmarck, the internationally known tapestry artist. Encircling those close attachments was his abiding love for people. Human beings were the ultimate subject of Niels Diffrient’s world-changing career. Calling himself an “ombudsman between the user and his circumstance,” he believed that product design should start with human needs and human experience and end with aesthetic considerations.

As a teenager he loved to draw. In his autobiography Confessions of a Generalist (2012), Diffrient remembered drawing a giant airplane on the back of an abandoned roll of wallpaper, rescued from the trash by his father. (How Cooper-Hewitt would love to have that drawing now!) It was the 1930s. Resources were short, but ideas were big. Unknown to the young Niels Diffrient, the new field of industrial design was taking shape at that same moment in the hands of Raymond Loewy, Walter Dorwin Teague, and Henry Dreyfuss. In 1955, Diffrient went to work for Dreyfuss in Los Angeles, after studying design at Cranbrook Academy of Art and collaborating with the young Eero Saarinen.

At the Dreyfuss office, Diffrient helped found the new methodology of human factors, commonly known as ergonomics. Designers use human factors to create products that fit the needs of people. At the Dreyfuss office, Diffrient led the creation of such legendary products as the Princess phone, the Polaroid SX-70 camera, and John Deere’s adjustable tractor seats. These innovative products took into account human psychology and physiology—Diffrient looked at the science of how people work in order to create products that work for people.

American Airlines aircraft markings

American Airlines aircraft markingsHenry Dreyfuss compiled the firm’s groundbreaking human factors research in the 1960 publication The Measure of Man, featuring iconic drawings of “Joe and Josephine” by Alvin Tilley. Continuing to study human factors in depth, Diffrient co-authored the Humanscale series of books and tools beginning in 1974 (MIT Press). These essential documents allow designers of products and environments to account for a broad range of human dimensions.

Photo by Sally Anderson Bruce

Photo by Sally Anderson BruceDesign historian Russell Flinchum, who organized Cooper-Hewitt’s definitive exhibition on Henry Dreyfuss in 1997, recalls, “Niels didn’t merely want to fill his boss’s shoes, but wanted to define his own role in his own terms. Devoid of bombast, he showed a quiet patience in explaining complex issues to designers and laymen alike.” Diffrient made his greatest contributions after becoming an independent designer in 1980.

The product that attracted Diffrient’s keenest attention in the second phase of his career was the office chair. A series of chairs for Humanscale created new ways to interact with task furniture. Instead of fussing with complex knobs and levers in search of a proper fit, people could now sit in a chair that responded to their own weight, adjusting spontaneously. (As Diffrient enjoyed pointing out, most people don’t bother to adjust their chairs anyway.) Cooper-Hewitt’s permanent collection includes Humanscale’s Liberty Task Chair (2007); its all-mesh back, tailored from three panels of non-stretch fabric, provides three-dimensional support for the spine. Diffrient also designed chairs for Knoll International and other manufacturers. His inventive is revealed in nearly sixty patents in the area of furniture design and mechanics. Caroline Baumann, Director of Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, commented “Amongst his countless design accomplishments from the Polaroid camera to submarines, Niels rethought the most basic component of office life. He improved people’s lives through the power of his designs, adding to their health, well-being and comfort. He was also a beautiful, curious human being himself, celebrating people and design at every occasion.”

Cooper-Hewitt was proud to honor Niels Diffrient with the National Design Award for Product Design in 2002. All of us mourn the loss of this great designer, colleague, and friend. We will remember him with fondness and admiration.

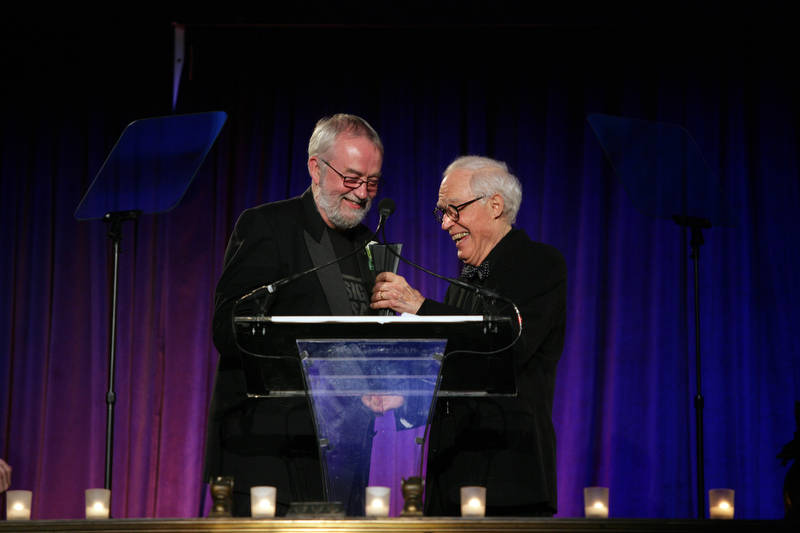

Niels Diffrient presents the 2009 National Design Award for Lifetime Achievement to Bill Moggridge. Photo: Richard Patterson

Niels Diffrient presents the 2009 National Design Award for Lifetime Achievement to Bill Moggridge. Photo: Richard Patterson