FEBRUARY: TEXTS

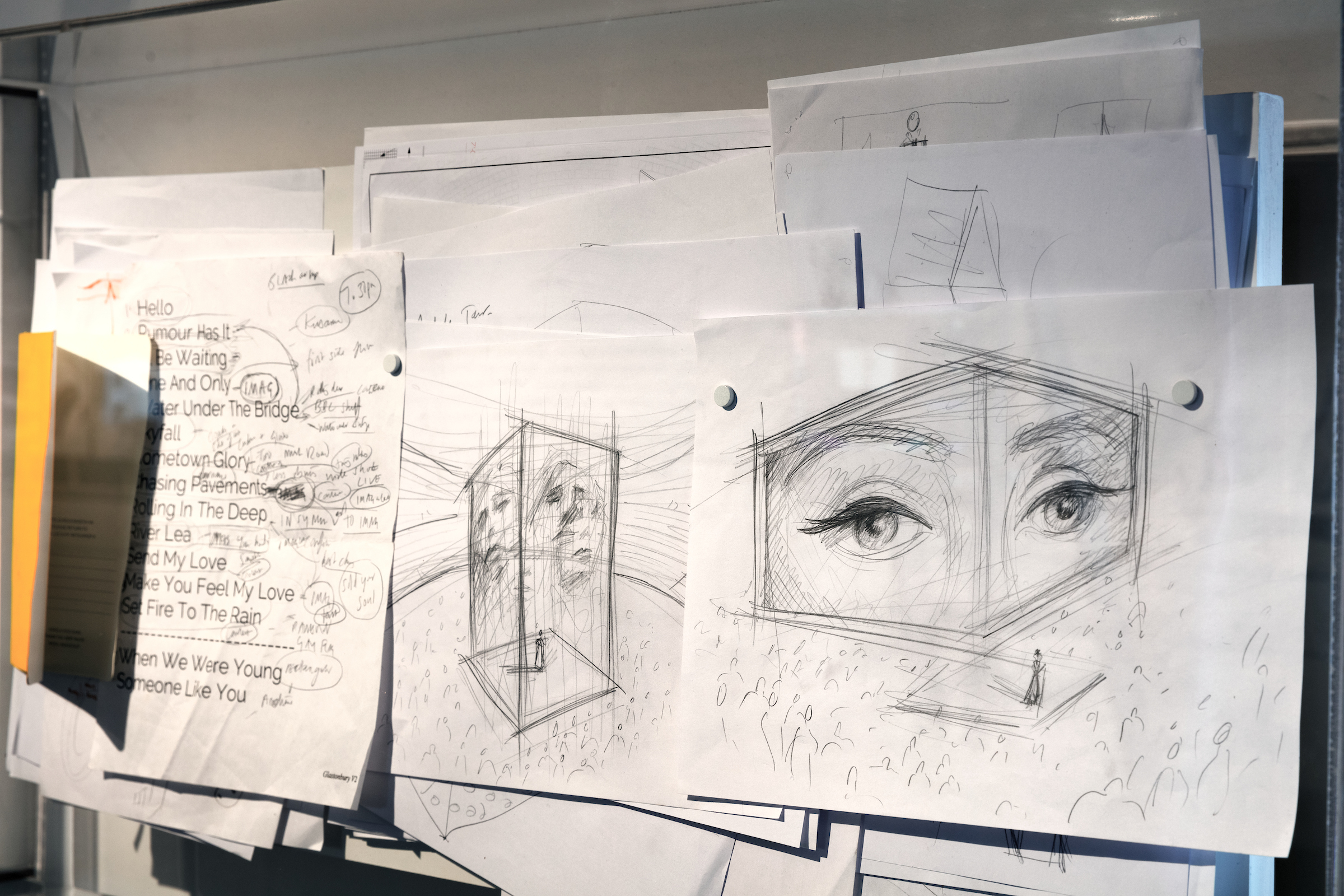

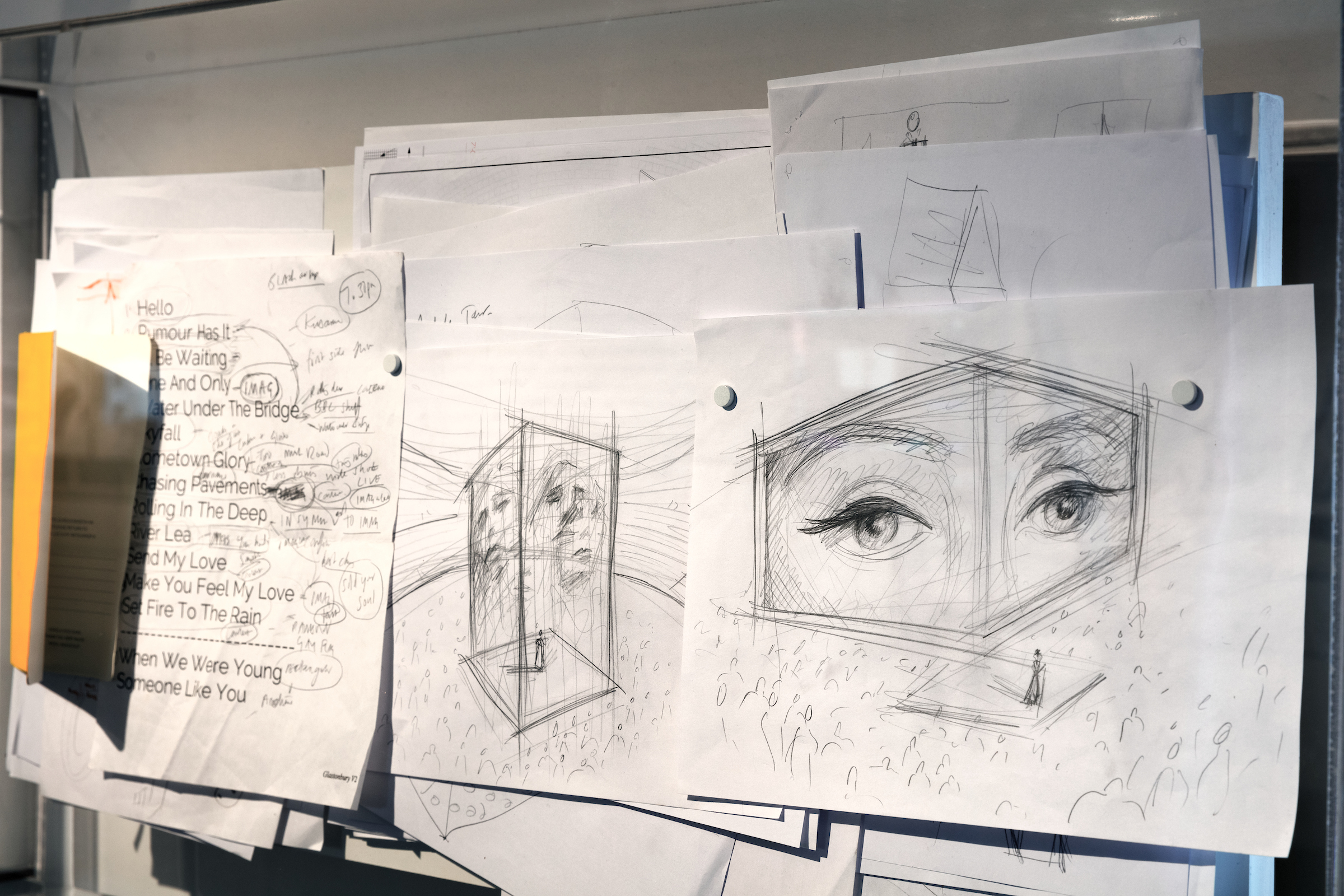

The act of reading is central to Es Devlin’s process for translating plays, operas, or song lyrics to stage designs or stadium tours. While reading, she underlines important passages and makes sketches in the margins of books. She returns to these notes as she considers the form of a stage sculpture or the narrative journey through an installation.

Reading provides us an opportunity to immerse ourselves in someone else’s thoughts. We imagine a world built by their words. On its own, reading can expand our thinking and open us to new understanding. But texts can also help spark our own creative ideas. The materials on this page encourage you to explore new ways to engage with texts as part of a creative practice.

Table of Contents

- Exercises: Writing and visual activities

- Related Reading: Highlights from Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library

- Programs: Exhibition tours, lectures, and hands-on workshops for visitors at all age and experience levels

EXERCISES

The exercises below are writing and visual activities to spark ideas by using—or generating your own—texts. These exercises are geared toward ages 15 and up, but all are welcome to try them out!

BIBLIOMANCY

Traditionally, bibliomancy refers to the use of books in predicting the future or offering spiritual guidance. Users choose a line or passage of a book at random and consider how that text might guide them. Here, we will use this technique as a creative writing prompt.

Pick a book from those you can easily access. You might pull one from your bookshelves or those of a family or friend. You can also use a school or public library. Open the book and place your finger down on a page at random. Use that line as your starting point in one or more of the following exercises.

If the first words you land on don’t spark your interest, keep searching at random until you arrive at something that resonates with you. As an example, we flipped through a collection of poems by Adrienne Rich titled Diving into the Wreck. We landed on the line, “Two women sit at a table by a window.”

Story Starter

Start to imagine a world for the line you landed on. Jot down any questions you might have or images that might come to mind as you consider these words. In our example, some thoughts might include:

- Do the two women know each other?

- How are they sitting? On chairs or a bench? Are they facing each other or looking out?

- What does the table look like? Where is the table? Is it in someone’s home? A public place?

- What’s beyond the window? Where are they? What can they see?

- Why are they sitting at this table? What might they do or say next?

Next, brainstorm some answers to your questions. How might those answers start to build an idea of a scene or story? If you’re stuck, look for places to create an obstacle or problem for your character(s). Force someone or something on the page to act. Here are some possible ideas based on our example:

- The women are old friends who are annoyed with each other, but neither wants to start a fight.

- They’re sitting at a table at a cafe in the city where they live; they can see people walking by on the sidewalk outside.

- They’ve met each other for lunch. One woman has finished her food, and the other is still eating. They’re about to argue over who will pay for the meal.

Try writing a short story or scene based on the answers to your questions.

Mindful Memory

As you consider the line you landed on, think about a memory or experience in your life that comes to mind in response. What does it make you think of? In our case, it might be a time we sat at a table with a friend or watched people sitting at a table nearby. Maybe the words make us think of a specific time of the year. We might remember a birthday party or special occasion. We might also think of a time we felt stressed or lonely.

No matter your memory, try to picture the specific place where you were and what you felt at the time. Feel free to invent some details if you can’t quite remember them. Start to write these details down. Try to fill a page writing whatever comes to mind as you consider this memory. If you feel stuck, consider your senses. What did you see, hear, smell, touch, or taste?

Repeated Searches

It’s okay to let your finger land on multiple lines. If you’re interested in gathering many lines, keep searching for lines that speak to you. You don’t need to limit yourself to only one book. Maybe you want to gather a pile and let yourself explore.

Write down the lines that you like or that provide a strong image. Review your collected words. How do they stand together on the page? Are there any themes or images that these different lines might have in common? Do they paint a picture of a particular setting or character?

Try to write your own description of this place or person. If you prefer a visual exercise, make a drawing or collage inspired by what you imagine based on this collection of words. You might even search for images online or in newspapers and magazines and save them to a mood board to represent what this place or person looks like.

SPATIAL WRITING

Written letters are a form of text that allow us to inhabit the life of another person. Today, we primarily send notes and messages digitally through email or text message, making handwritten letters more personal and rarer to receive. Some of us may not even write by hand at all in our daily lives. Due to the slower nature of handwriting letters, it creates a space where we can express feelings more intimately and reflect on our own lives, and even invite us to write more than we usually would in an email.

Get started

Take a look at Alfred Frueh’s 1913 letter to his fiancée Giuliette Fanciulli from the Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

Alfred Joseph Frueh. Alfred Joseph Frueh to Giuliette Fanciulli, 1913 January 10. Alfred J. Frueh papers, circa 1880-2010. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

About the letter:

While traveling, cartoonist and illustrator Alfred Joseph Frueh would send letters to his fiancée Giuliette Fanciulli. He sent this love letter to her on January 10, 1913. In the letter, Frueh describes an art gallery Fanciulli would soon visit. To enhance his text, Frueh folded the paper so that his letter could become a small 3D model of the gallery. He cut, collaged, and folded paper to create the gallery walls, artwork, and even a coat check.

In this exercise, you will write a letter about a place that you want to share with someone, and then create a 3D representation of that space using your letter.

1.Write a draft of your letter

In your letter, write about a place that is special to you, somewhere new you have visited or moved to, or a place where you experienced an exciting or important moment in your life. Explain why this space is important and describe in detail what this space looks and feels like.

Here are a few questions to get you started:

- Who are you writing your letter to? Is it a friend, family member, an old mentor, or someone you haven’t talked to in a long time?

- Why is this place important to you?

- What does this space look like?

- What can you see, hear, touch, smell, or maybe even taste in this space?

- How do you feel when you are in this space? What emotions come up?

- What details might you be able to represent visually in your model? What details might be easier to explain through text?

2. Create a rough prototype of your space

How will the space you described in your letter inform how you create a representation of that space?

First, roughly sketch your space on a piece of paper from a bird’s–eye point of view. Consider the number of walls in your space. What elements are key to include and what can be left out? Is your space a rectangular or square room like Frueh’s? Or is it outside? If so, consider how you could create a 360° view of your space. For example, you could create a circle where the paper doesn’t fold, or perhaps multiple folds, creating a hexagon.

Second, with a spare sheet of paper or two (that’s the same size or similar to what you will use for your final letter), play around to figure out the dimensions, folds, or cuts you might need to make to your letter to construct your space. Use your sketch as a guide for how many folds you need to make or where ends of the page will meet. Think of this model as a pattern that you’ll follow to create your final letter.

Once you have developed a rough model of your space, consider how you will provide instructions for the recipient on how to build the space. You might provide written instructions or make tab indicators to tell them where to fold and connect paper.

3. Construct your final space

Referring to your rough prototype as a guide, fold and/or cut your letter paper to construct your space.

4. Write the final draft of your letter

Unfold your paper and write your final letter. Make sure you are not writing on the side you will be drawing on.

5. Draw your final space

Flip or fold your paper over and draw your space. Think about what you described in your letter. Draw those details and consider even drawing yourself in that space. You can use any medium from markers and pencils or photos and collage.

RELATED READING

FROM Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library contains more than 80,000 volumes, including books, periodicals, catalogs, and trade literature dating from the 15th through the 20th centuries. Now that’s a lot of text! The highlights below showcase annotations by industrial magnate Andrew Carnegie and a historical exploration of the ultimate writing tool.

A Carnegie Anthology, arranged by Margaret Barclay Wilson

Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919) was an American industrialist and philanthropist. He was born in Scotland and emigrated to Pennsylvania with his family, where he started his career as a telegraph messenger boy. Later, he made railroad investments and built a fortune in the steel industry. He donated millions of dollars to libraries and universities. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum is housed in his former home, which was built in New York City in 1902.

A rare find, this edition of A Carnegie Anthology —pictured below—collects years of Carnegie’s quotations. Privately published in 1915 by the author, Carnegie inscribed on the first page his intention to “mark by his own hand” this personal copy. Throughout the book, he underlined and commented on his own published words.

Notes on reading: Imagine what you would write on your own biography if someone else were to author it. Grab a book you read previously and give it another read. Did you write notes in it? Do you agree with your former opinions?

Fountain Pens: History and Design, edited by Giorgio Dragoni and Giuseppe Fichera

A writer’s greatest instrument, besides their mind, is their pen. A writing implement spans generations of time and space. This book lets us understand the history of the fountain pen through its evolution and design.

Notes on reading: Highly fashionable in its time, the fountain pen is still considered a collectible item. Do you have a favorite pen or writing tool? Have you used it to be creative recently?

PAST PROGRAMS

Cooper Hewitt hosts a range of programs—including exhibition tours, lectures, hands-on workshops, and others—for visitors at all age and experience levels. Videos of recorded programs are available here.

Learn more about upcoming programs at Cooper Hewitt.

11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. ET

2 E. 91st Street

New York, NY 10128

1:30 p.m. to 2:15 p.m. ET

2 E. 91st Street

New York, NY 10128

11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. ET

2 E. 91st Street

New York, NY 10128